Todd Bartel in front of Pollination of Devonia, (Synterial series), 2002, gallery talk, L(and) exhibition, Room 83, Watertown, MA, photo courtesy of Ellen Wineberg

Todd Bartel came to serious collage because of an assignment he received on the first day of his first class as a freshman at RISD. He recalls the desks were strewn with magazines, and as soon as the course started, Professor Hardu Keck gave the students a prompt, “Create five collages that work with the following sentence: Surrealism is the chance happening of finding an umbrella and a sewing machine on a dissecting table.” Keck did not mention he was quoting Andre Breton, who was quoting Comte de Lautréamont (Isidore Lucien Ducasse). He expected his students to work with the strangeness of visual combination and found imagery. That was Todd Bartel’s introduction to Surrealism and chance coupling. He fell in love with collage immediately, coming up with forty-five collages by the first week. One of the key elements that draws him to collage is that it can involve a vast array of analog and digital technologies. “I consider myself an Omni-coupler,” he says.

Consume, 2020, uncollage, inkjet print, Epson Enhanced Matte Paper, detachable acrylic frame, Sugar Maple, 18 x 24 x 6 inches, installation view at Beals Preserve, Art on the Trails—Rising Up exhibition, curated by Hilary Zelson, Southborough, MA, photo courtesy of Todd Bartel

It is quite evident in your work and in your texts that you are passionate about collage – idea, history, and technique. You focus on the relationship between landscape, or as you coined – landview – and collage. What is collage for you and how do you see its relationship to landviews?

Collage is the infinite possibility of combining things. When combined, any two (or more) things result in a transformation—a third thing. That is what I love most about collage. It teaches you ways of coupling, and it often suggests technologies through combination. Many of the things I make are well outside of my training in painting and it takes an attuned eye to see possibility. Opportunity is omnipresent for anyone who is resourceful and open to it. Traditionally, students of art are instructed to study nature; I take my instruction from the potentials of collage.

How did I connect collage with landscape? I love working with paper, and I love working with wood. After two decades of exploring these materials, I awakened to their interrelation, which continues to raise questions that drive my studio practice. While not all collage is paper-based, paper as a collage material is the predominant idiom, which got me thinking: paper comes from woody plant fibers; wood comes from trees; both come from the landscape—cut and hacked from the land. I love history and have read extensively about both genres, and in 2004 I realized they were two separate histories that intersected in the 1960s and 70s with Environmental Art. As a result, I now consider myself a collage-based eco-artist.

I coined the term “landview” in 1995 as a dissenting concept to the artist’s term “landscape”—a Dutch and Germanic technical word for “created and shaped” images of land. “Landscape,” to quote John Brinckerhoff Jackson, “first meant a picture of a view; then the view itself.” I found that particular word evolution problematic because landscape’s etymology has connotations of “cutting, hacking and shaping,” which led me to wonder about “viewing” a tract of earth that is “untouched” by humans or otherwise protected from human activity. We also tend to separate ourselves from the definition of nature, and we often divide our actions from natural processes. Considering our place in nature and the dubious ways we sometimes use the term “landscape,” inspired my Terra Reverentia series and all the work since.

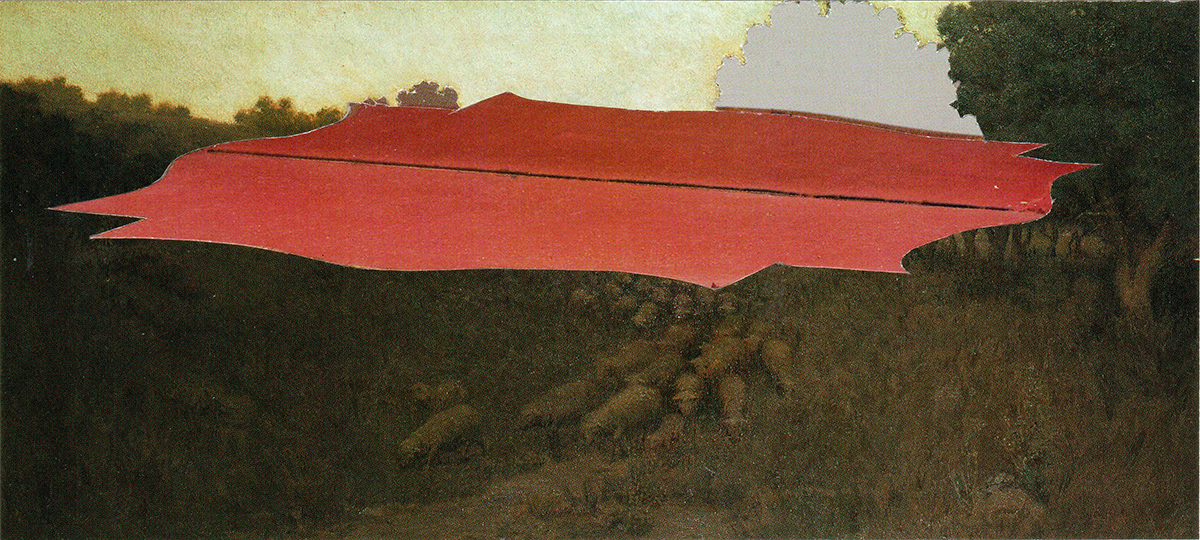

In disagreement with the idea of humans removing themselves from the definition of nature, the Terra Reverentia is a series of oil paintings of appropriated medieval land backgrounds. I removed all the people and buildings and then boxed and framed them with various materials and imagery juxtapositions. While finishing up that series, I developed a want for a new word, which inspired a search for an alternate suffix. I should note, of course, now, during the third decade of the twenty-first century, we recognize that Earth has been shaped by human intervention during our short tenure on the planet. Everything has been touched by human activity, but when I coined “landview,” I had not heard of the term “Anthropocene” yet.

In contrast to land-shaping, the etymology of “landview” uses the Proto-Indo-European root, “weid”—to see, wise, wisdom, way of proceeding, manner, view—a view designed to encourage human mending strategies, especially when it comes to cutting timber. For me, collage, assemblage, and installation practices provide inexhaustible possibilities for creating work that raises questions about the seemingly unrelated histories of collage and landscape. I have been working to pull both histories into the same timeline for close to three decades now, and that idea has kept me busy with serial work.

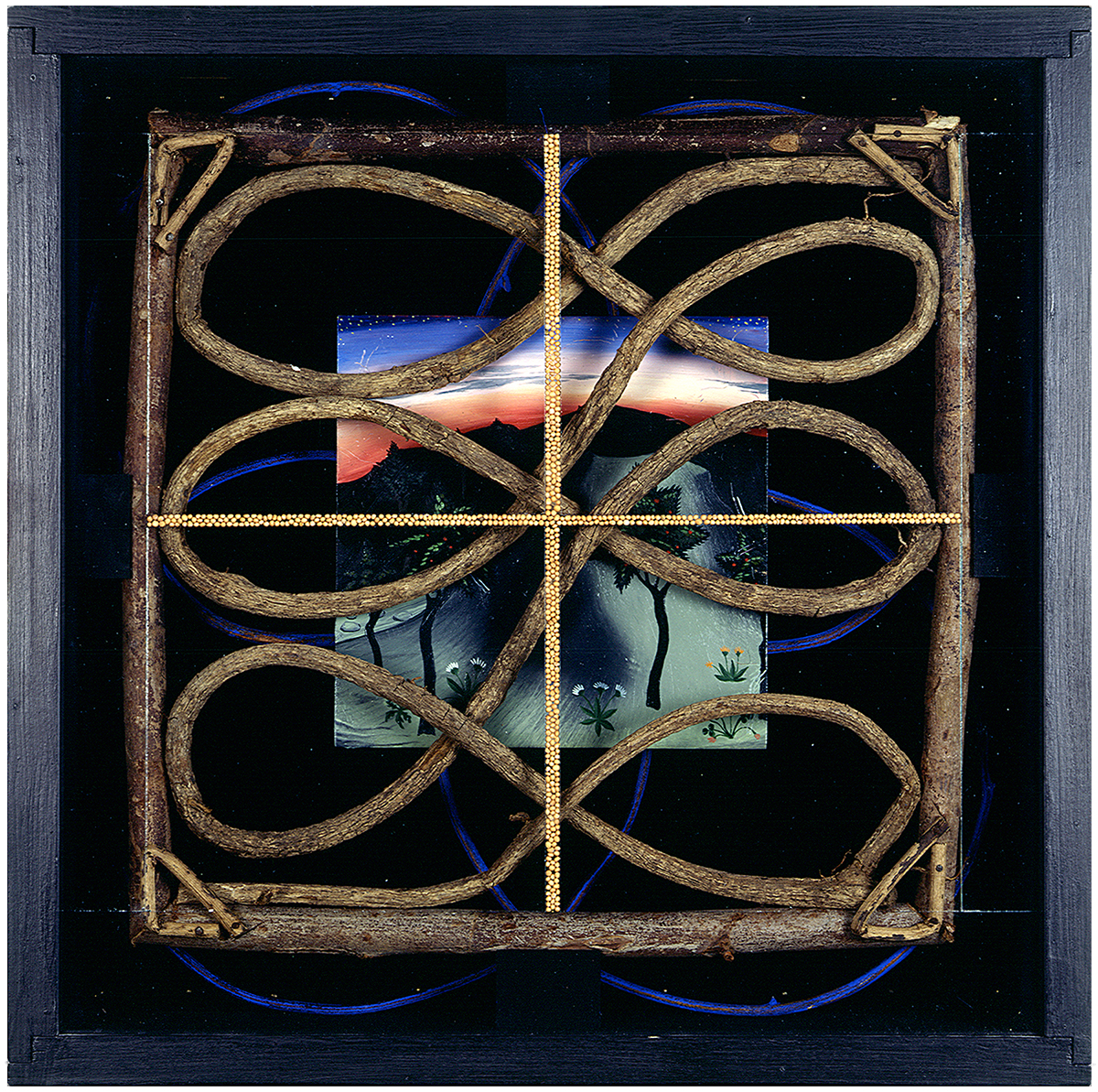

Terra Reverentia: Recrudesce, 1995, constructed wood box, tempera, velvet, vines, oil on wood, gold leaf, branches, glass, mustard seeds, 15.5 x 15.5 x 3.5 inches, photo courtesy of Todd Bartel

Tell me about the body of work in your recent exhibitions at Room 83 in MA and Stand4 in Brooklyn and your show at the show at Beals Preserve.

The show at Room 83 (Watertown, MA) provided me an open opportunity to select a grouping of my work for L(and). (Splitting the word “land” before the first syllable reveals an analogous word for collage along with the prefix of landscape in a single word.) I decided with the Curators Cathleen Daley and Ellen Wineberg to select representative pieces from many of my series work. Since my last solo show in 2003, L(and) provided an opportunity to group the fruit of my studio practice exploration of the previous two decades. On view were select works from my Synterial, Salvage, Transplantation, Witness, Garden Study, Real Landscape, Removed Presence, and Landscape Vernacular series, respectively.

Artist/curator Jeannine Bardo curated Landviews of Commonplaces at Stand4 (Brooklyn, NY), in which I exhibited several pieces from my Landscape Vernacular series alongside your work and Katrina Bello’s. Landviews of Commonplaces was an important show for me because Bardo used my neologism as the basis for the show’s title, which is a first for me. In her catalog essay, she writes, “Language, like land, is forever forming and reforming, buckling under seismic forces of change, rising and merging and traveling and transforming…Bartel’s critique [of the word landscape]…offers us a counter meaning that instead promotes ‘viewing,’ ‘re-looking’ and ‘respecting’ land.”

Curator Sarah Montross (Interim Artistic Director/Senior Curator, deCordova Museum) included my most experimental work in her Art on the Trails show entitled Mending. Located at Beals Preserve (Southborough, MA), I installed an earthwork entitled, This Is A Landview. For this piece, I created a two by nine-foot stencil, cut the shape of Helvetica letters into the earth, and then turned and smoothed the soil to spell: “weid-.”

Installation view at Stand4, photo courtesy of Todd Bartel

This Is A Landview, 2021, installation view at Beals Preserve, Art on the Trails—Mending exhibition, Southborough, MA, cut earth, turned soil, Helvetica, 2 x 9 feet, photo courtesy of Todd Bartel

In Synterials, you enhance the beholder’s experience of your collages by containing them into double-sided artist-made frames that open and close. This dimensionality adds spatial and kinetic elements that engage the viewer physically. What is the genesis of this series and what can you share about the process?

Not until you posed this question did I consider my folding frames within my Synterial series. The jury is still out because, while I rather like the connection, I must admit I think of the folding frames outside the Synterial project. The folding frames were developed because I frequently make puzzle-piece-fit collages that extensively utilize the versos. For that purpose, folding frames are just a practical necessity. I conceived the idea for my first Synterial—a frame shape that echoes or points to the content of the work it frames—while earning my MFA. Back then, I imagined the idea of making a frame that had a bridge to another frame. But it took me ten years and a personal experience before I realized that idea. When I finally set out to make it, it was a challenge to imagine how to make the frame because all aspects of the project had to be known first—otherwise, how big and what shape to make the frame? I decided to call the first frame a “Synterial” because I had to synthesize everything simultaneously, at least the known parameters and components, before building the actual frame. The overall process felt more like designing a building and coordinating its construction or directing a film which is also dependent on the contributions of others. I had to develop everything upfront before the frame could be conceived as an actual object; the synthesis of all materials yielded the series title. There is an in-depth interview by Nance Van Winckel titled “The Box Does Not Need To Be Square” about the Synterial series if readers are interested to learn more.

Proportions and Table Manners, [Landscape Vernacular series] 2014, burnished, interlocking collage, 19th-century papers, end pages, marbled papers, Xerographic prints on antique end pages, toner transfers on rain eroded bulletin board papers, canceled stamp and envelope remnant, pencil, antique cellophane tape, archival document repair tape, yes glue and dictionary definitions, artist-made folding-frame, 24.5 x 19.125 inches, photo courtesy of Todd Bartel

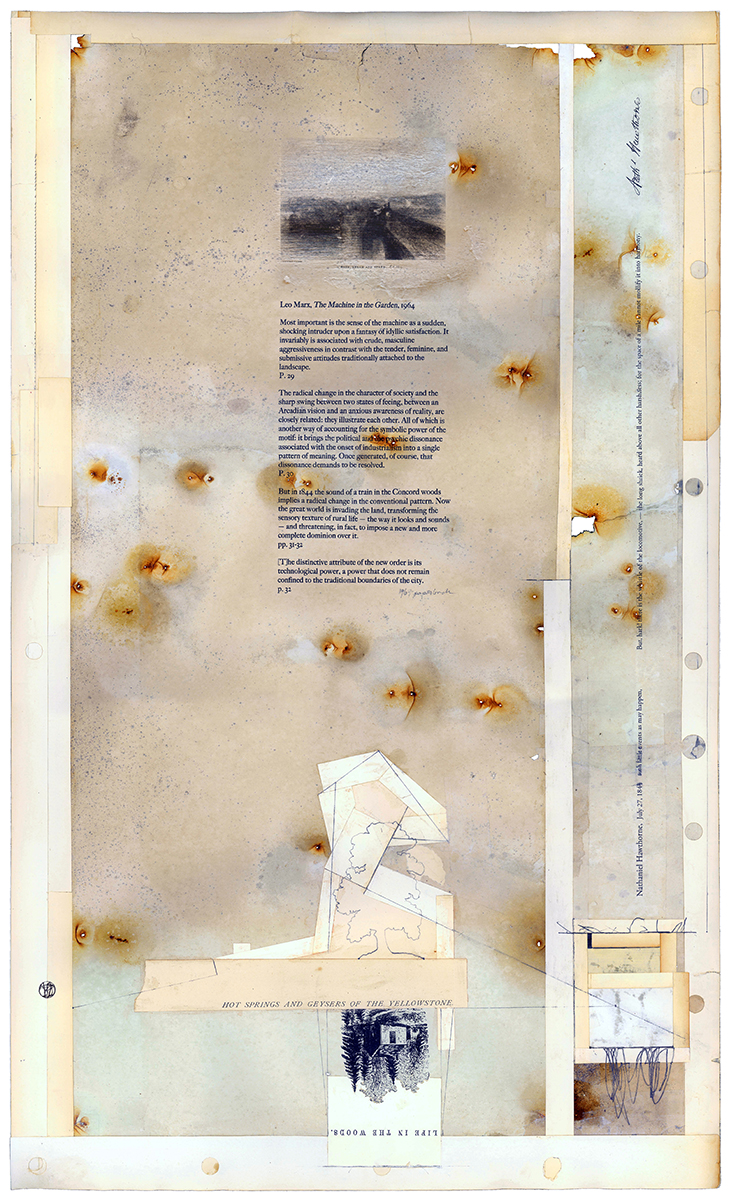

In the Landscape Vernacular series, you address the history of land depiction, specifically the changing attitudes about land use and ecology. This involves research, accumulating data, and editing. Tell me about your research process and how is it expressed throughout this series?

I collect books, dictionaries, engravings, antiques, and all things paper-related, which fuel all my series work. I also collect discarded books, specifically to harvest the end-pages. My resource materials are made up of analog and digital materials, which are filtered into dossiers, and which eventually get used in the collages, assemblages, Synterials, or whatever project is at hand. I should point out that I often re-publish my resource materials. I make high-resolution scans and print them onto period paper end-pages to achieve contemporary facsimiles of the originals. Sometimes I use actual engravings or book pages in my Landscape Vernacular (LV) collages, and at other times I use re-published copies. Whenever I am able, I obtain multiple copies of my materials to keep an original out of circulation while others get used up in the work itself. As a result, I now have an extensive library of ephemera, books on collage and landscape, and a vast digital library that informs my work and research.

In the past ten years, I have made a concerted effort to collect original texts and objects expressly acquired to establish a Wunderkammer or museum that examines these fields. I hope to show such materials one day in connection with a more in-depth examination of my work.

The LV collages always center upon definitions of selected words. I’m interested in the combination of text and image. I would also like to point out that the word illustration originally meant “verbal description.” “Illustration” expanded to mean “a picture” due to Grangerization and the proliferation of the scrapbook. The LV series juxtaposes vintage ephemera from the 18th- through the 21st-centuries set within the limitations of a puzzle-piece-fit collage to extra-illustrate problems about land use throughout Western history.

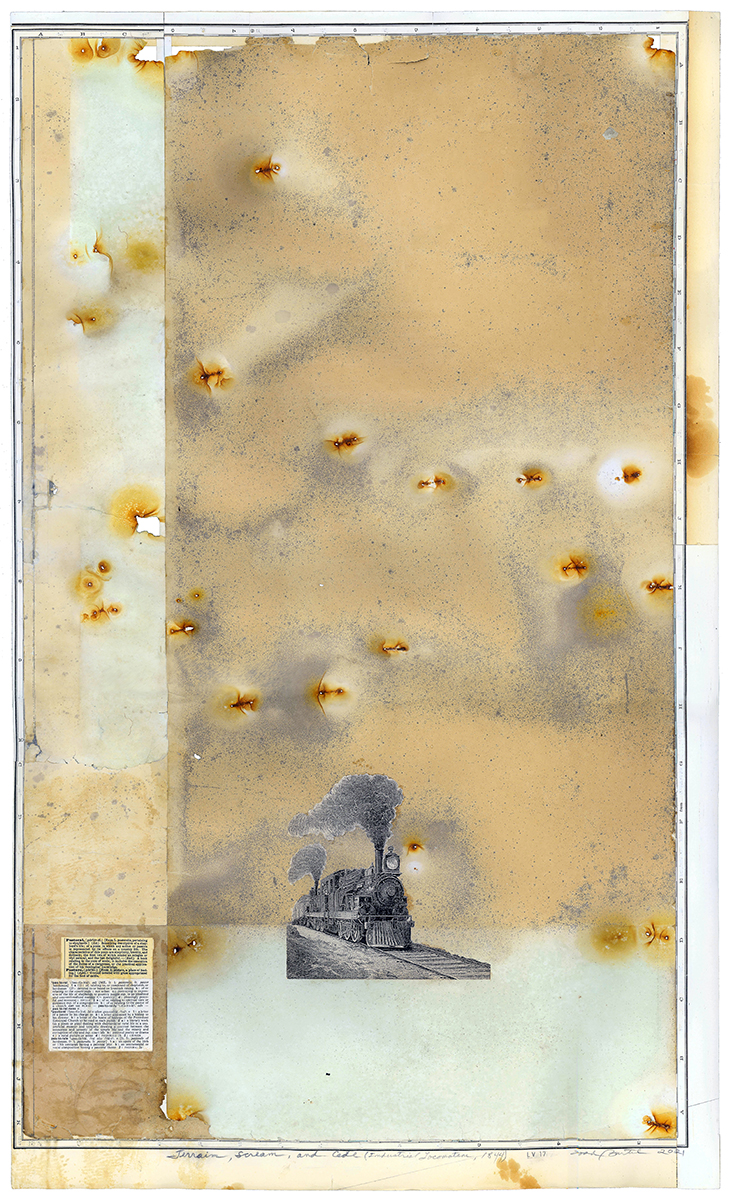

Terrain, Scream and Cede—Industrial Locomotion 1844, 2021, burnished interlocking collage, xerographic-transfers on 19th-century endpapers and rain-washed, weather-beaten bulletin board paper with staple rust, map graticules, dictionary definitions of “pastoral,” pencil, wax paper transfer, Yes glue, document repair tape, 27.5 x 16.5 inches, photo courtesy of Todd Bartel

Terrain, Scream and Cede—Industrial Locomotion 1844, 2021, verso, photo courtesy of Todd Bartel

In Witness you create rule-based series of puzzle-piece-fit collages, aiming to achieve zero waste during the process of making these diptych collages. What is the idea behind this project and what drove you there?

In the early 2000s, I began to audit my studio practice. I realized that collage always produces waste, and I wondered how to forge a more mindful approach to waste management within my creative process. Pushing beyond my regularly using negative shape remnants, I started thinking about reducing, reusing, and recycling as a conceptual strategy. My entry point was a mental comparison between Herman Melville’s The Whiteness of the Whale (1851), Raymond Roussel’s Impressions d’Afrique (1910), John Cage’s 4’33 (1952), Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953), and Arvo Pärt’s Tabula Rasa (1977). Each of these works offered insight into minimalism and reflection, and that informed particular ways of working. I thought about these works for about two years before doing anything, and ultimately, I think I pulled from each in some way. I devised ways to incorporate all production parts in an end-product, ruminated on all aspects of an idea upfront—including materials and all processes involved—and became mindful of the beginning and the end before ever setting out to work.

Eventually, the idea of cutting on top of two pieces of different colored paper simultaneously came to me because I realized, multiple-page, simultaneous-cutting yields identically shaped pieces that can be exchanged. Puzzle-piece-fit collage, or “interlocking collage”—to credit artist/curator Cathleen Daily with that distinction—was born out of that thought exercise. There is zero paper waste when the only cuts you make are identical for all pieces of paper used, and the resultant pieces are exchanged evenly. Interlocking collage technologies and using my waist materials have led me to many projects. Witness was the first series that came out of that inquiry. I call the series Witness because the onlooker can only see the unequivocal exchange between location and object when seeing these positive and negative spaces in tandem. I also can’t help but think about trees witnessing furniture made of its own wood and furniture witnessing the deforestation from whence it came.

The titles of the Witness series are obnoxiously long, but they too are rule-based, and they make a point about paying attention to where things come from. I use the actual titles of the objects, which come from auction house catalogs, and I couple them into a single title, however long they may be.

Witness 15a, Frederick Judd Waugh’s Circa 1900 ‘Curling Waves,’ with A Circa 1770 Chippendale Tabletop, and Treetop Negative Space, 2021, burnished interlocking collage, auction house catalog cuttings, watercolor, document repair tape, 2.875 x 6.5 inches, photo courtesy of Todd Bartel

Witness 15b, A Circa 1770 Chippendale Carved and Figured Mahogany Serpentine-Front Five-leg Card Table with Shaped Fragment from Frederick Judd Waugh’s Circa 1900 ‘Curling Waves,’ 2021, burnished interlocking collage, auction house catalog cuttings, watercolor, document repair tape, 10 x 8.75 inches, photo courtesy of Todd Bartel

What are you working on in your studio these days?

Currently, I’m working on several Landscape Vernacular collages in preparation for a solo show at Anna Maria College in 2024. I’m thinking about juxtaposing the definition of “no man’s land” with imagery of the moon or the planet Mars. I am also considering including the definition of my newest neologism: “unland”—the de-classification of land as a thing that can be owned; a change in the status of territory that was once thought to be owned but cannot be owned in actuality.

Todd Bartel received a BFA from Rhode Island School of Design in 1985 concluding his studies at RISD’s European Honors Program in Rome. He earned an MFA in Painting from Carnegie Mellon University in 1993. Bartel has taught at Brown University, Manhattanville College, Carnegie Mellon University, and has been a visiting critic and artist-teacher at Vermont College, New Hampshire Art Institute, and Leslie MFA in Visual Art programs. He has lectured at Alfred University, Western Connecticut State University, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Montclair State University, Chatham College. His work has been exhibited nationally in venues that include Palo Alto Art Center (Palo Alto, CA), Katonah Museum (Katonah, NY), Brockton Art Museum (Brockton, MA), The Rhode Island Foundation (Providence, RI), Zieher Smith (New York, NY), Mills Gallery (Boston, MA), Iona College (New Rochelle, NY). He is the founder and Gallery Director at the Cambridge School of Weston’s Thompson Gallery, Installation Space, Community Gallery, and Red Wall Gallery. A seasoned teacher since 1986, Bartel currently teaches drawing, painting, collage, assemblage, conceptual art, and installation art at The Cambridge School of Weston, Weston, MA.

Etty Yaniv works on her art, art writing and curatorial projects in Brooklyn. She founded Art Spiel as a platform for highlighting the work of contemporary artists, including art reviews, studio visits, interviews with artists, curators, and gallerists. For more details contact by Email: artspielblog@gmail.com