Natalie Moore grew up in San Diego, California, and spent many summers in Norway with her mother’s family. Although she has lived in New York for much longer, the dramatic Californian and Norwegian landscapes remain a lasting influence. Climate and ecology have also become more present in her work over the last decade, as the climate crisis worsens and governments and corporations continue to minimize the effects of carbon emissions, pollution, water use, and chemical waste.

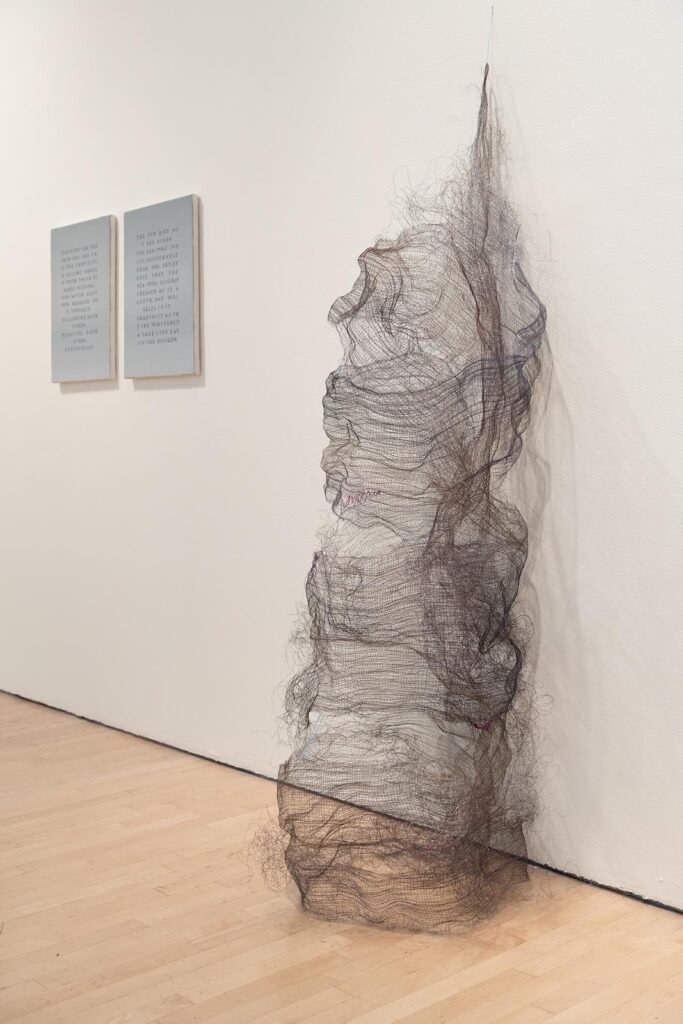

These concerns come through in her materials and in the way her forms hold a tension between stability and collapse. Working with industrial and hand-built elements, often woven and shaped into open structures, Moore creates surfaces that shift with light and movement, moving from sharp focus, thinning out, or disappearing from view.

Your website organizes the work into categories—dry, wet, and mend—they feel like ways of thinking. How did you arrive at this structure, and how do these themes talk to each other in your practice?

I created those categories about a year ago when I was updating my website and noticed that those themes kept repeating themselves over the years. Dry and Wet are directly related to landscape and climate change – oceans and deserts, droughts and floods. The sculptures take these ideas to extremes, seen in the series titled Dry, which imagines shapes that are vaguely botanic and drained of all water, possibly tossed around by sandstorms, yet at the same time lyrical and in the midst of movement or change.

Tell us about the Cecropia tree leaves series.

I went to Costa Rica for an “eco” residency in 2021 and became obsessed with the leaves of the Cecropia tree. I was amazed by their giant silhouettes in the sky and their strangely curled leaves on the ground. Investigating these curled and ruffled leaves that have fallen over thirty feet to the ground became a passion. Within a day or two, the leaves dehydrate, curling into themselves until they are twisted forms as small as six inches long. This change I observed differs from some of the other changes to natural forms that I am interested in, but in other ways, it is similar.

While rain and wind may change the profile of a cliff over centuries, sudden storms and surges can alter the forms of trees, land, and man-made structures in just minutes or hours. While these leaves have not been directly affected by the elements (fire, wind, rain) in the same way, they are affected by dehydration and dry out. The dry leaves are a microcosm of how the lack of water has changed the shape of reservoirs, lakes, and rivers in the western US and the southern hemisphere due to global warming. The environmental effects from a lack or excess of water can result in both beautiful and heartbreaking changes.

Water plays a central role in your imagery. Can you elaborate on that?

I have always lived on a coast. Watching the rhythm of the water ebb and flow calms me when life gets too intense. I was recently in San Diego visiting my mother, and found the tide pools and shapes of the cliffs more beautiful than anything I could ever hope to create. My Wet series — on the flip side of drought — deals with floods. Hurricane Sandy and Irene rapidly flooded whole New York City neighborhoods, including my own. Several of my recent pieces (drip, flood) imagine water rising up the sides of the buildings and pouring in from cracks and crevices. In many others (wave, river, spill), I am thinking about the effects of water pollution and contamination from factories, dyes, oil, and plastics. Both of these themes are ways of dealing with my own fears and concerns, while also wrestling with the dichotomy of the “terrible yet beautiful” realities in this world.

You also reference icebergs in your work.

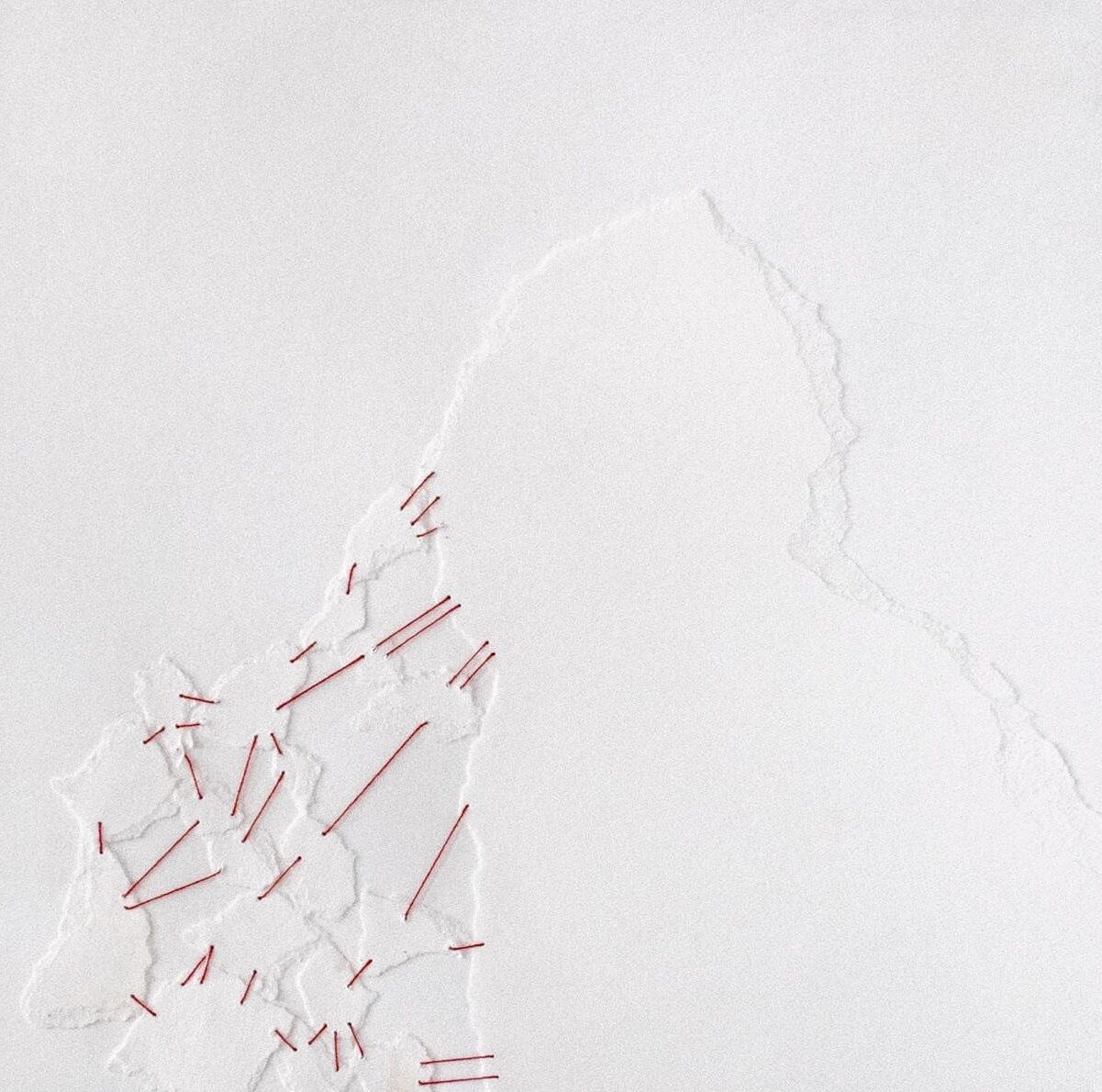

I know we cannot sew the icebergs and glaciers back together, but I made a series of works on paper during the pandemic that aims to try. I like to think of mending as a rebellion against rampant consumerism and waste, a culture that throws away so much that can be fixed, patched, and renewed. These are major issues: how to dispose of waste, global economies, toxicity, water and air pollution, underregulated manufacturing practices, and so many other “wicked” problems that I cannot solve, but making work helps me to think through them in my own way.

Pathways and Boundaries are other recurring themes in my work, as I mentioned, my mother came over from Norway when she was in her 20s, and my paternal grandmother came to the US from Russia during the revolution. My hometown of San Diego sits on the border of Mexico. In NYC, people come from all over the world, and I have always been fascinated with how people migrate, where they come from, and where they land.

Tell us about the drought portraits. How did you develop this series?

I came across that work from two directions. As I was experimenting with natural dyes from food waste and local vegetation, dying fabric and making ink for works on paper, the droughts in California and around the world reached record levels. I became interested in the views of the Colorado River and Southern California reservoirs, which provide drinking water and irrigation water. I found the changing water levels stunning and began creating a portrait gallery using dyes created from crops that rely heavily on irrigation to flourish. For some of the works, I used the river and reservoir contours, referencing bodies of water such as Lake Mead, El Capitan, Lake Powell, and the Salton Sea. Avocados are notoriously thirsty, so I made a few pieces using the ingredients for Avocado Toast: salt, lime juice, and avocado pits and skins for dye.

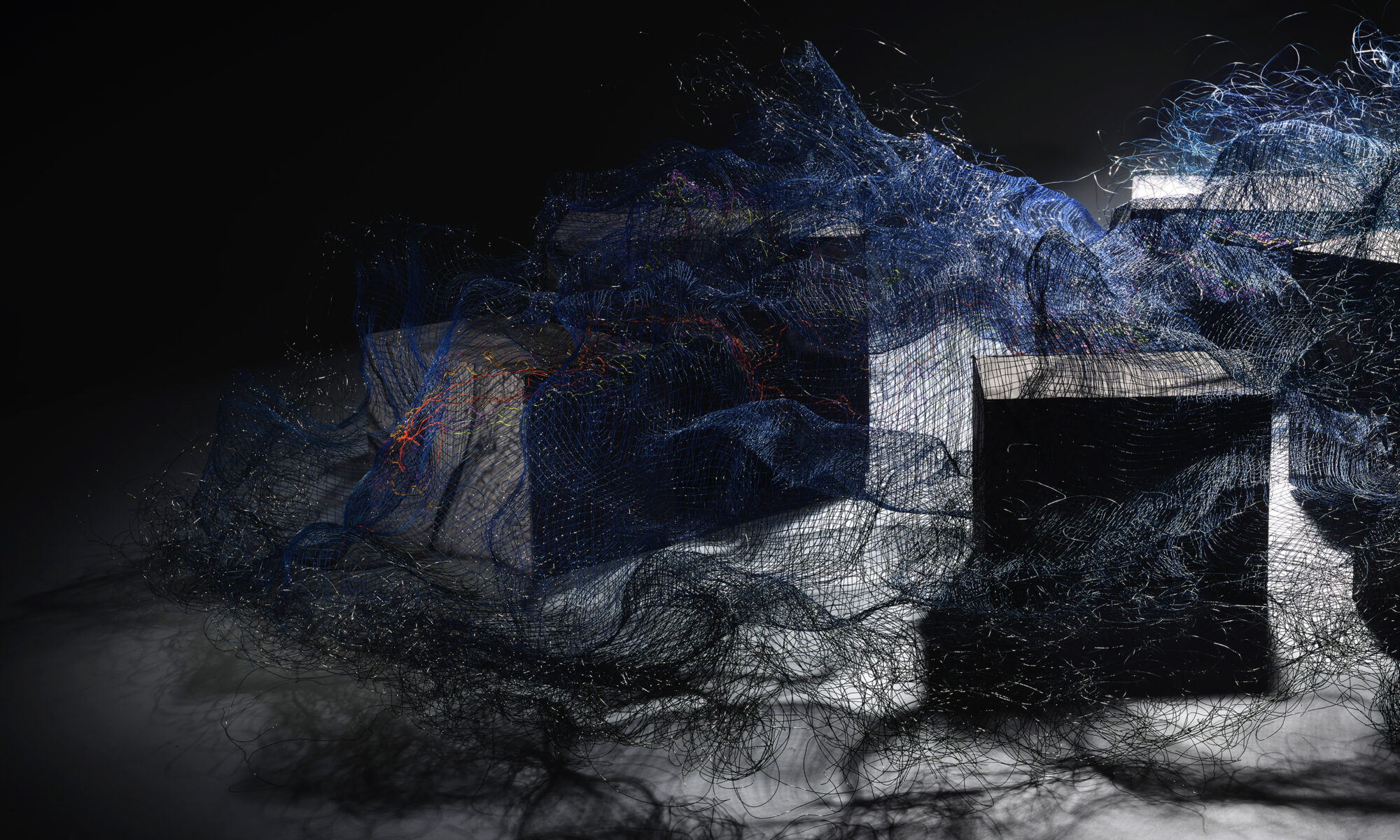

Going back to the water imagery, the flood installation seems like the flip side of the drought work. What does someone experience when they walk into that space? How did you create that feeling of flooding?

I was excited to have the opportunity to create a piece for The Boiler, a space that has so much character and history. I had already made a piece in my studio where the imaginary leak was in the corner (Drip). I thought the rectangular divot in the wall would be an effective place to imagine water pouring in. I made a few scale models in my studio, watched waterfall videos, and then tried to create a sense of water rising up the exterior walls and pouring in, using the wire mesh.

Wire appears throughout your work in so many forms: woven, barbed, drawn. In the Woven Wire sculptures, especially, you’re taking something industrial and putting it through this deliberate, hand-based process. Walk us through how you actually do this, and what wire means to you as a material?

Wire has become my pencil. I started using barbed wire just after grad school, and I have found that the variety of weights and materials (steel, copper, aluminum, raw, coated) offers endless possibilities. Wire is flexible and malleable, allowing me to draw in space.

The woven wire sculptures began after becoming frustrated with the regularity of the industrial steel scrim I had been using. I wanted the scrim to be a little less perfect, revealing flaws and fissures, able to tear and unravel. I tried fraying the scrim and pulling it apart, but it was too well-made, and I could not manipulate it the way I wanted. So, I tried to figure out how to reverse engineer the grid. I was awarded a residency at the Textile Arts Center in 2012 and began weaving wire on various looms. This was met mostly with failure, until I learned about one of the oldest loom designs (c. 4000 BC) and constructed a very primitive warp-weighted loom. I still use the same basic loom design to construct my work. What I gained was complete control of the density in the grid, and since I built the loom each time, I could make lengths of mesh to the exact dimensions I needed. With my current way of working, I lose a bit of the moiré and scrim effects, as it is not as regular or as tight as the manufactured mesh.

Scrim shows up in both your sculpture and your drawings. What is scrim, and what drew you to it? What can you do with scrim that you can’t do with other materials?

I fell in love with scrim many years ago when I visited the Getty Museum with my Father soon after it had opened in the late 90s. In one of the exhibitions, they had used hanging scrim panels as signage. I was fascinated by how it could appear solid, yet at a different angle or under different lighting conditions, appear completely transparent. I began focusing on how it is used in theatre and started experimenting with sharkstooth scrim in my studio. I was trying to figure out how the material could capture the sense of a mirage or a dream, something so sharp in focus that could suddenly disappear. This eventually led to purchasing large bolts of steel mesh used for sieves and filters, and spray painting them to give them color. Although I’m not using the actual scrim much anymore, I still find it magical how light can completely transform our perception of the material.

“Mending” is both a theme in your work and sounds like it might be an actual process. What does mending mean to you?

Flaws and irregularities are seductive to me. I am not drawn to the overly slick, produced, or perfect. It is the minuscule irregularities that make me smile inside. It is one reason I chose not to use the manufactured scrim in my work; it was somehow too perfect.

In my work, mending is very visible, whether through the use of feminine craft practices to imagine repairing an architectural space, as in the interventions for the Textures of Feminist Perseverance exhibition at the James Gallery, or in the falling and mending drawings and plaster sculptures. Thread, like wire, forms a linear connection between forms; it is also a material that we encounter every day in our clothing.

I studied a bit of Japanese art history when I was an undergrad. I was introduced to the concepts of kintsugi and sashiko, which I found quite beautiful both conceptually and aesthetically. A couple of years ago, I traveled to Chile for a residency in the Atacama Desert. Before the residency, I saw the exhibition Quiebres y Reparaciones (Breakdowns and Repairs) in the Santiago Pre-Colombian Art Museum, which spoke to me. Mending is used in many cultures for practical, decorative, and funerary purposes and likely exists in every culture, but this was the first time I had seen an exhibition from a perspective rooted in the Americas. I find scars and repairs beautiful; they are a testament to time and experience. And, in our day and age a rebellion against overconsumption and waste.

What are you working on now?

Recently, I have been wanting to create a piece inspired by smog and fog, which were significant parts of growing up in Southern California in the 1970s, before emission regulations were put in place. Smog was responsible for the most gorgeous sunsets and the shroud of orange that hovered over Los Angeles. Here in Brooklyn, we had a little taste of that orange sky when wildfire ash came down from Canada, so beautiful yet so toxic.I am working on a few things. I finally finished a piece, Spill, that I have been working on and off for the past six months. I have been researching ocean waste and pollution, thinking about the horror and beauty of an oil slick, waste runoff from mining and textile processes, and have some other pieces at the early stages, taking these ideas in different directions. I am also working on newer ways of using dyed yarn and thread with the wire, similar to the piece Tug of War, which incorporates fibers dyed with local vegetation in Chile, and is woven with copper wire. I am also very excited to collaborate with the choreographer Ava Desiderio for Norte Maar’s Counterpointe 13 at the end of March.

About the artist: Natalie Moore is an artist and educator working in Brooklyn, NY. Her practice includes sculpture, works on paper, and installation. Moore has exhibited her work nationally and internationally since 1987 at diverse venues such as The Boiler, Brooklyn NY, The James Gallery, NYC, Shirley Fiterman Art Center, NYC the Spartenburg Art Museum, SC, artMoving Projects, NYC, the Textile Art Center, NYC, Gallería Arté Mexicano, Mexico City, Mexico, White Columns, NYC, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, NYC. She is a recipient of grants and awards from the Pollock/Krasner Foundation, Pratt Institute, Textile Arts Center, and Artists Space. Moore’s work has been featured in Sculpture Magazine and CNN International and reviewed in several publications, including the New York Times, New York Newsday, and USA Today. Moore received an MA in Studio Art from NYU in 1992 and a BA in Fine Art from the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1987. @nataliegmoore

About the Writer: Etty Yaniv is a Brooklyn-based artist, writer, curator, and founder of Art Spiel. She works in installation, painting, and mixed media, and has shown her art in exhibitions across the United States and abroad. Since 2018, she has published interviews and reviews through Art Spiel, often focusing on underrecognized voices and smaller venues. @etty.yaniv