In early September, painter Deborah Zlotsky pulled off what few artists even attempt: two solo shows opening at once, on opposite sides of Manhattan. The Light Gets In filled McKenzie Fine Art on the Lower East Side, while Genealogies took over Kathryn Markel Fine Arts in Chelsea. A double dip in one city, on one calendar page. It might sound like a scheduling accident, yet standing in front of her candy-striped canvases, the simultaneity feels deliberate. Zlotsky thrives on overlap: order brushing against disorder, geometry trembling at its edges, patterns that carry memory while stumbling into the present.

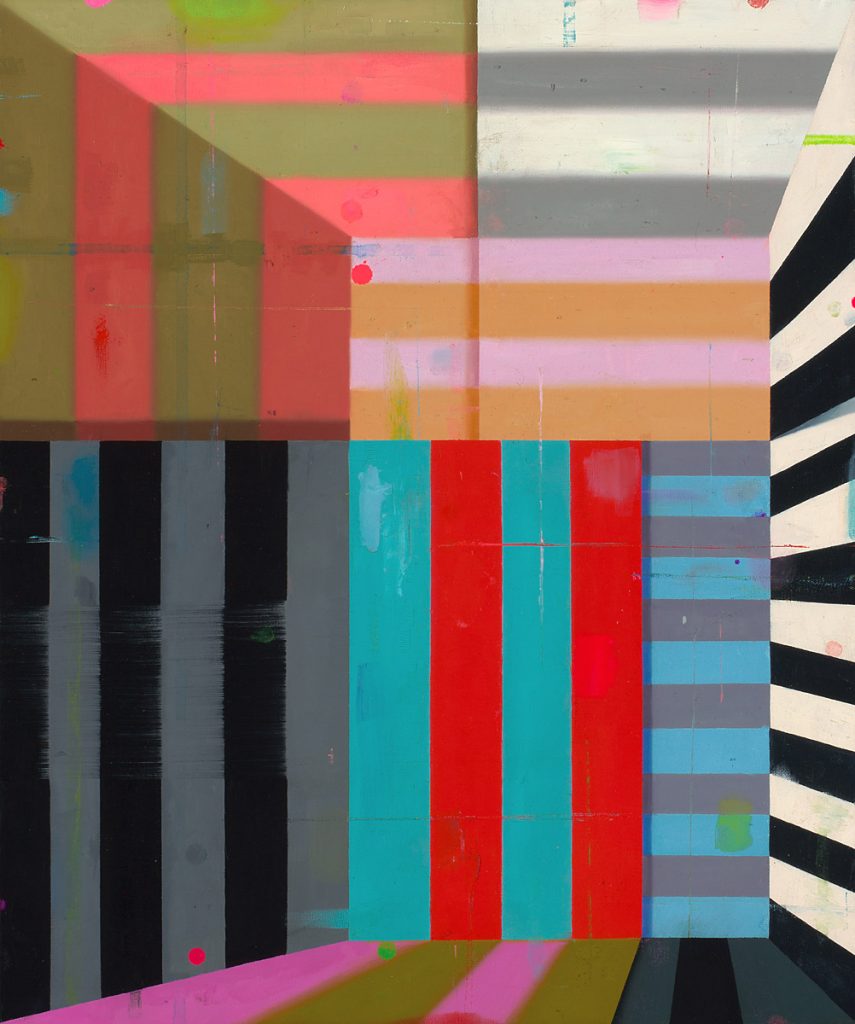

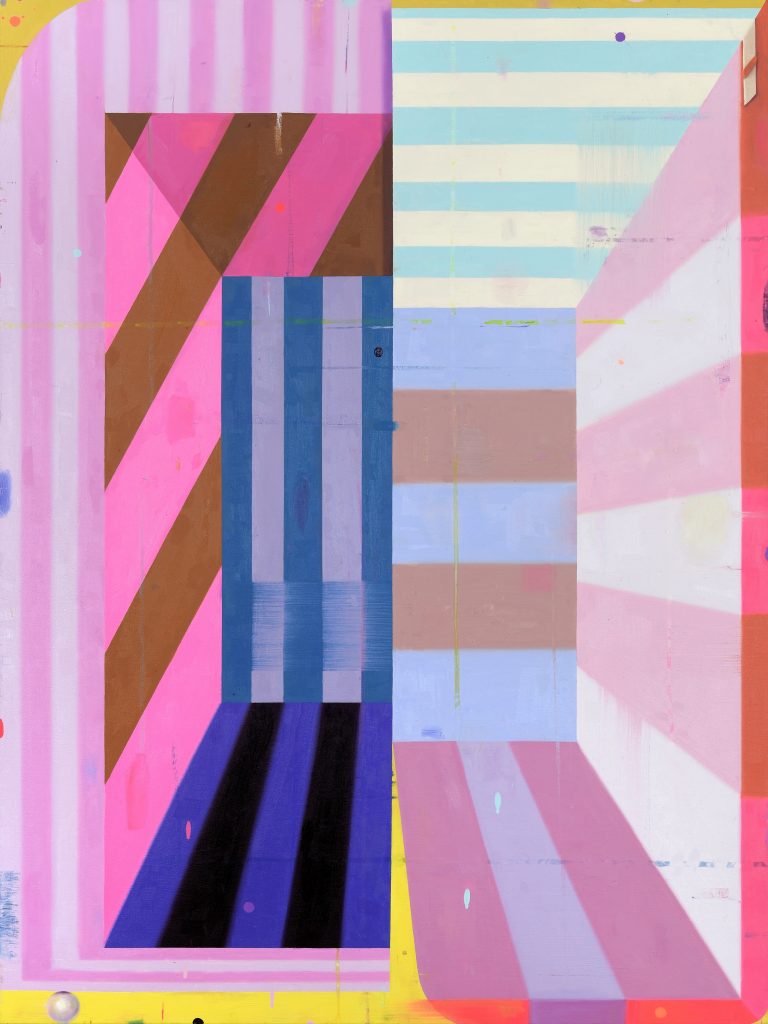

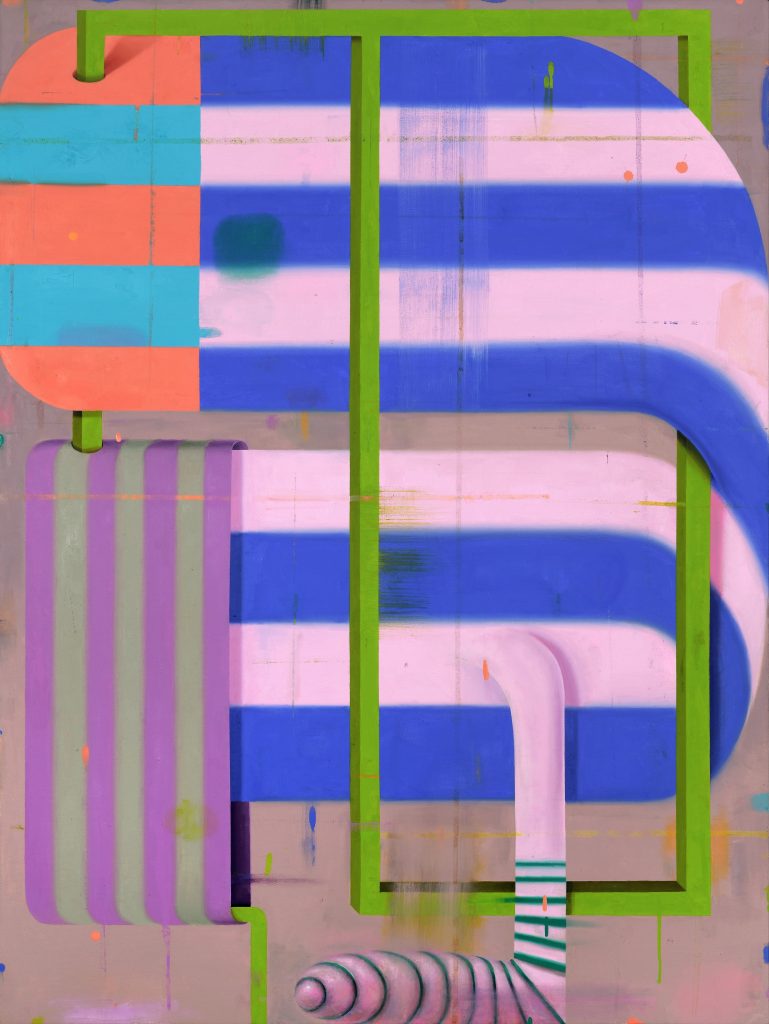

The shows don’t read as repetition. They are fraternal twins: different temperaments, same DNA. One series keeps its shirt tucked in, rectilinear, boxy rooms striped and shadowed, with the occasional string or bolt like a belt holding everything in place. The other lets loose, piling shapes into unruly stacks and tangled genealogies. The titles wander too, Not a Line but a Constellation, Tragedy Plus Time, as if each canvas had its own eccentric relative to introduce. Together, the two exhibitions stage Zlotsky’s favorite drama: history pressing against now, leaving marks, drips, scars, and beauty.

That instinct to juggle two modes at once is not just on the canvas, it runs through her life. Petite, dark-haired, and a very youthful sixty-three, she looks like she might be swept away by a nor’easter, yet she managed the artist’s equivalent of two Broadway nights in the same week. “At first it was daunting,” she admitted. “I went down rabbit holes that didn’t seem substantial enough. Then I came up for air and just started painting.”

The split freed her. The Light Gets In is tight, precise, sometimes claustrophobic. Genealogies is looser, slightly tipsy in its balance, more narrative in the way one stripe trips into another. Zlotsky sees them as “adjacent and simultaneous, the same vocabulary, just different protocols.”

Stripes are never innocent. They are prison uniforms and beach towels, chic Parisian shirts and danger tape. Zlotsky knows this. Her stripes wobble between the chic and the punitive, the playful and the institutional.

“Stripes are patterns and cycles at their most reductive,” she said. “Patterns and cycles of history, neurological patterns, family and generational patterns. The paintings are a way to hold disparate parts together, despite shifting orientations and colors. They suggest psychological or historical patterns, layers, and timelines. Things that don’t go together but must.”

Stand back and you see terrain, like a warped map. Move closer and the stripes fracture into something more intimate: muscle fibers, fabric, scars. Valerie McKenzie, her Lower East Side gallerist, puts it this way: “As your eye travels across the paintings, moving from crisp and sharp passages to softer, blurry moments, the experience is akin to memory, and how it shifts from clarity to haziness. And the trompe l’oeil elements, the strings, the pearl, the drop shadows, are subtle and gently playful.”

That slipperiness is what Zlotsky courts. Her pleasure lies in setting up a system, then tilting it off balance. Rectangles blur, tilt, or sprout strange props: string, tape, shadows that don’t belong to anything. Why build order just to watch it buckle?

“I see the hard and soft edges as changes in perception,” she explained. “History is always losing ground to the present, even though it is foundational to it. Like a memory piercing through a moment unexpectedly. It all co-exists.”

None of this was evident from the start. Zlotsky studied art history at Yale, not studio art. Painting came later. “When I shifted from art history to painting, I felt so behind,” she said. “By the time I finished grad school, I was maybe at the sophomore level of an undergrad program.”

Teaching became her crash course. Now a professor at RISD, she designed classes that pushed students toward abstraction and, by necessity, herself along with them. In 2019, she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in Fine Arts, a recognition that cemented her place among leading contemporary painters. “I had to stay a half step ahead of my students,” she said. “Eventually I realized I felt more free, more curious, more at one with reasons for making work.”

Illusion still lingers. She can’t resist a drop shadow or a fake pearl, but abstraction gave her permission to chase urgency instead of verisimilitude.

Home base is Albany in New York’s Capital Region, where she splits time between teaching, painting, and walking the dog. Her studio fuel is not silence but audiobooks. “As much as I love painting, it’s the listening to the story that gets me into the studio for long hours,” she said.

If her stripes could sing, they would be scored by Motown, R&B, disco, and Broadway. She lights up talking about Pixar’s WALL-E blasting “Put on Your Sunday Clothes” from Hello, Dolly! “That’s the weirdness and tone of my inner soundtrack,” she laughed.

Color itself has taste for her, literally. Zlotsky is synesthetic, wired to experience taste as color. Her palette often comes from childhood candy: sour gummies, bubble gum, sugar bursts. Jolly Rancher pink with licorice black.

For all the sugar-burst palette and disco soundtrack, life barges in. In early 2020, she found herself racing to escape the COVID lockdowns in Bogliasco, Italy. “I have a photo of the Rome airport screen listing all flights canceled except ours,” she said.

Life has constantly intruded: motherhood, caregiving, academia, bills, and yet the paintings kept coming. “Making the work made me feel as if the craziness of it all was nourishing and necessary, even if overwhelming,” she said.

Her canvases juggle contradictions with ease. Stripes tilt, colors clash, geometry unravels, but the whole holds. They are maps of how to live with sweetness and sorrow, memory and immediacy.

Her time-machine fantasy is not Florence or Weimar but something louder, sweatier, more excessive. “Studio 54,” she said without hesitation. “The late 70s, when I was a teenager, the music, the spectacle. That would be fun.”

So here we are: one artist, two shows, candy-colored stripes holding entire genealogies of memory and mess. A soundtrack of disco and Motown. A sensibility that refuses tidy closure.

Zlotsky’s work is about staying upright while the geometry slips, about remembering while forgetting, about holding together the pieces that never really fit. Two shows at once? Of course. The simultaneity is not a quirk of scheduling, it is the point.

Make your tax-deductible donation today and help Art Spiel continue to thrive. DONATE

The Light Gets In is on view at McKenzie Fine Art, 55 Orchard Street on the Lower East Side, from September 5 through October 12, 2025 (mckenziefineart.com). Genealogies is on view at Kathryn Markel Fine Arts, 179 Tenth Avenue in Chelsea, from September 4 through October 11, 2025 (markelfinearts.com).

About the writer: Laurie Gwen Shapiro’s new narrative nonfiction book, The Aviator and the Showman, about Amelia Earhart and her husband, George Putnam, was published by Viking on July 15. An excerpt appeared in The New Yorker in early June. @lauriestories

Related articles:

https://artspiel.org/why-black-art-is-rarely-just-abstract/

https://artspiel.org/judy-pfaff-taught-them-to-break-the-rules-now-theyre-sharing-the-stage

https://artspiel.org/sensuously-severe-why-artists-call-don-voisine-the-real-deal/