In Tirtzah Bassel’s vibrant and challenging exhibition, I Put A Spell, the viewer is immediately confronted with the question: Can the power of witchcraft—rooted in both ancient wisdom and intuition—serve as a potent metaphor for reclaiming women’s agency in art and beyond?

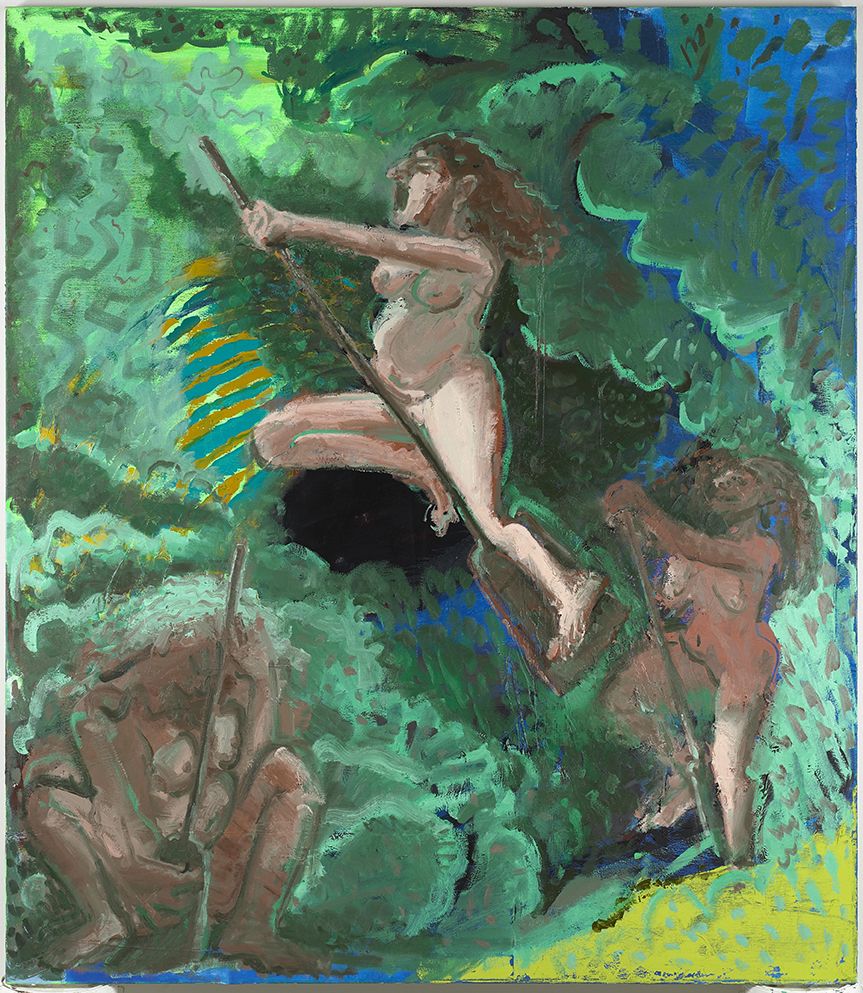

A group of paintings installed right at the gallery door, as an introduction to the space, offers a few clues about what lies beyond the wall. In a large painting of three witches, their naked bodies occupy the frame as they hang out in the woods. One is flying on her broom with her mouth gaping open, as her two friends below leisurely lean on their brooms. To the right-hand side of this panel, four small gouache drawings are hung together like a storyboard, each describing a nude woman sweeping the floor with a broom and taking little pleasure in it. The broom is either liberating or oppressive, depending on your witching skills.

Bassel explains that The Broom (After Fragonard) was the first painting she created in this new body of work, and that when she finished it, she felt it was risky to show, as it was too easily ridiculed. “A witch on a broom? Come on,” she thought. But this moment of discomfort was a key to a breakthrough, as is often the case in an artist’s process. Rather than shying away from it, Bassel decided to explore the source of discomfort. She asked herself why images of women in liberated, unconventional roles and postures still provoke embarrassment. Such responses might be rooted in the broader structures of power within the art world and the world in general, where traditional narratives have long been dominated by male perspectives that are often internalized by women. In this series, there is not one male figure; all of the women are unapologetically naked, wild, fleshy, and moving in space with complete freedom. They come in all shapes and sizes, ages, and colors. They sit with their legs spread, unbothered by exposing their body, as they climb trees, play together, weave baskets, and suppress wild beasts.

Bassel’s technique: the loose brushstrokes, bright colors, and thick paint, is just as liberated as her witches. The brushstrokes convey a sense of spontaneity and movement, capturing the witches’ unrestrained energy and dynamic spirit, hinting at casual chaos. This dialogue between the medium and the subject deepens the artwork’s impact. The witch serves as a metaphor for the artist, putting a spell on us viewers through a series of moves. Bassel recalls another interesting parallel between witches and the “other”: the traditional image of the witch, as it emerged in Europe in the Middle Ages, overlaps with the stereotypical image of the Jew from the same era: a curved nose, a pointy hat, and a suspicious spiritual practice.

In this exhibition, several pieces mark Bassel’s departure from the canonical imagery of Renaissance paintings and old masters. Her infatuation with witches led her to seek out images of rituals and fantasy that preceded Christian iconography. Recalling the scriptures she studied as a child in an Orthodox Jewish household, Bassel realized that many of the texts she recited described miracles and rituals meant to bring these about. Some of them have a guest appearance in this exhibition: The ritual of the scapegoat at the temple, performed by the high priest, is depicted in a medium panel showing a woman tying a red string to the goat’s horn. The tale of Honi the circle drawer, a pious man who saved his community from drought by drawing a circle and standing in the center, begging God for rain, is present in Circle Maker. Here, a woman reclines on a bright red background, drawing a circle around herself. Traditionally, women do not perform these rituals in both the original texts and Orthodox practice. However, in Bassel’s paintings, they boldly claim this sacred space, performing the rituals themselves. The most striking example is in the “Binding” series of small-scale acrylic-on-paper sketches. Nude female figures are busy wrapping themselves with Tefillin, the small leather box containing Hebrew texts on vellum, worn by Jewish men at morning prayer. The sacred straps envelop them head to toe, around their breasts and between their legs.

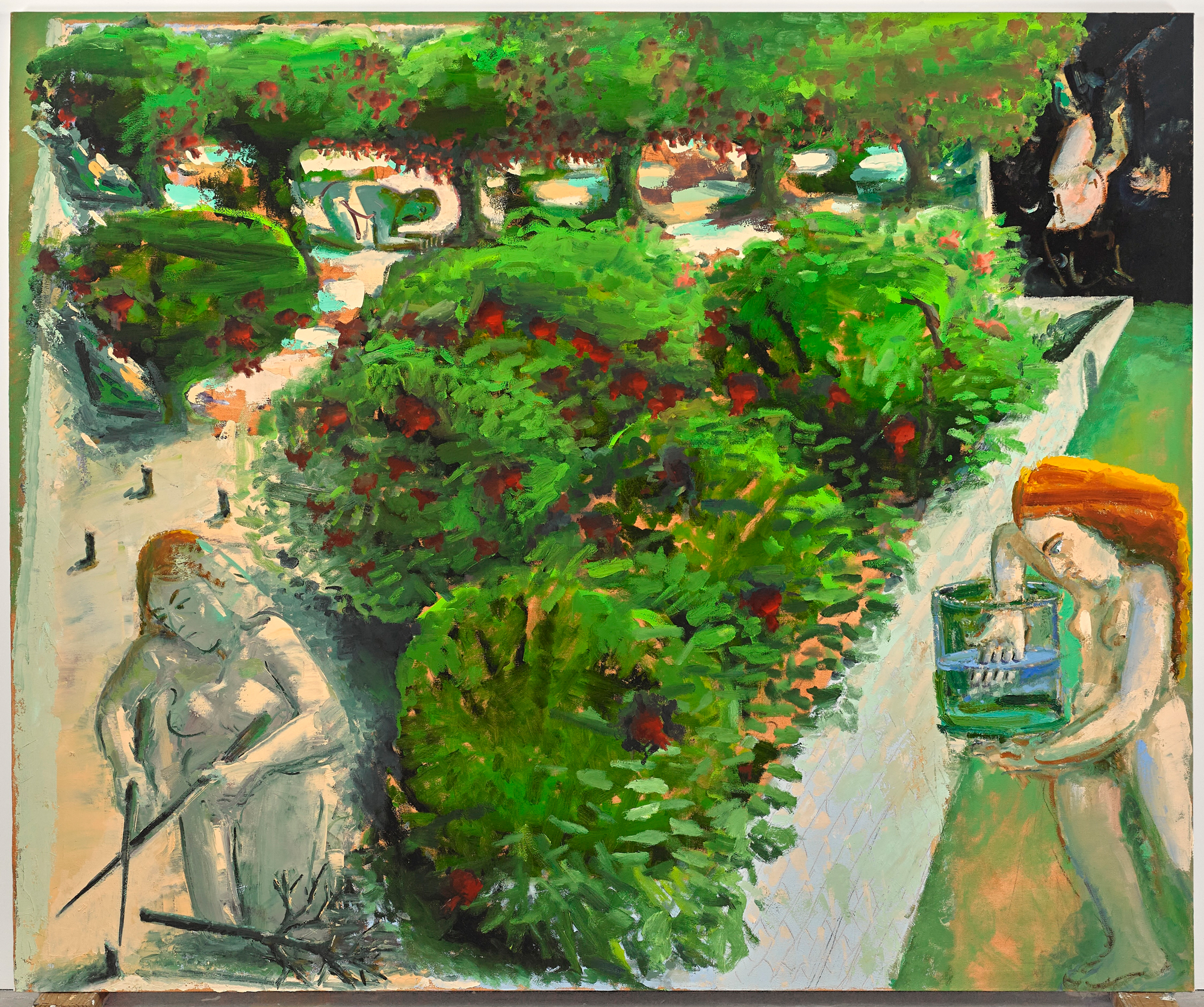

In a large panel titled Four Entered The Orchard, Bassel adapts a Talmudic tale about four rabbis who enter the orchard, each with a different outcome: one looks and dies, another is harmed, a third cuts down the trees, and the last one enters and leaves in peace. In Bassel’s painting, these adventurous roles are assigned to women. The orchard, a symbol of secret mystical knowledge, becomes theirs to explore, showcasing their imaginative potential to inhabit and transform traditional narratives. This contemporary reclaiming of ancient rites invites viewers to reflect on their own cultural histories, highlighting the enduring power of myth and its role in shaping both personal and collective identity. By offering these traditionally male-dominated spaces to women, Bassel mirrors how mythic narratives can be reinterpreted to empower those marginalized. It is a call to the audience to see their own stories and struggles within these timeless tales, fostering a deeper connection to the art.

This group of paintings feels like an open bacchanal. You can hear sounds of cackle and laughter, the ‘woosh!’ of broomsticks cutting through the air, and arrows shot from the sky. Bassel’s women are outdoors in lush gardens or floating in pure color. They make strong and purposeful movements, echoed by the direction of the brushstrokes on the surface. Bassel is a choreographer, a stage designer, and a storyteller, inviting us into her dynamic, savage universe, where ancient myths and stories of profound wisdom are performed, with all lead roles taken by women. I cannot wait to see where she takes us next.

Tirtzah Bassel: I Put A Spell, January 10 – February 8, 2026, at A.I.R Gallery, 155 Plymouth Street, Brooklyn, NY, Wed–Sun, 12–6 pm

Artist talk: Tirtzah Bassel in conversation with Aliza Rachel Edelman; Wednesday, January 21 at 6:00 pm

About the writer: Noa Charuvi is a New York City-based artist specializing in painting landscapes, architectural ruins, and construction sites. She is an occasional contributor to Artspiel. Noa holds an M.F.A in Fine Arts from the School of Visual Arts in New York and a B.F.A in Fine Arts from the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem, Israel. Her paintings are included in “Landscape Painting Now,” an anthology of contemporary paintings published by D.A.P and Thames & Hudson. Charuvi was a recipient of the Pollock Krasner Foundation Grant in 2018.