New York City loves a label the way it loves a line outside a new restaurant: there is the promise of significance and the reassurance that someone else has already decided what matters. The label flatters, then quietly ends the conversation. The oil painter Rifka Milder’s work refuses that bargain. Call her a “downtown painter,” and you’re not wrong, but her new solo show at Helm Contemporary, GREAT JONES, is what happens when someone who actually grew up downtown, in a household run on paint and argument, makes abstraction that declines to become neighborhood branding. Art in America once called her “an oil painter’s painter.”

Gallerist Karina Argudo has been making smart bets on midcareer abstraction at Helm. The gallery sits in a spare third-floor loft on the Bowery near Grand, perched above a sushi spot and a matcha shop. You climb a set of old, slightly ill-tempered stairs, the kind that remind you the building was here long before the gloss arrived. From the windows, the Bowery stages its familiar argument in real time: wholesale grit and glassy reinvention, with the New Museum nearby expanding again. Tourists drift toward “downtown authenticity,” but the street itself refuses to pick one identity and settle down.

Just a few blocks away, Milder’s second-floor studio is above La MaMa, the experimental theater temple that has never met a quiet moment it could not improve with shouting. The day I walked over after a longer look at the show, actors were bellowing down the hall. Milder barely registered it. She knows exactly what she has: a north-facing window, great light that keeps repainting the streetscape.

Milder has two grown kids, but she reads younger: wiry, alert, attention switched on. It is the same alertness the paintings have. I had seen earlier work at Rosebud Gallery in Chelsea, but the paintings in this solo show feel newly tightened, pulled toward the middle, as if the canvas itself is asking for order and she is willing to negotiate. “The new work is a paring down,” she told me at her crowded opening, pleased I noticed. “A concentration.”

Her largest work, ANDROMEDA, is pure muscle, a 72-by-96-inch canvas that holds the room, sunburnt gold and hot mustard, with looping green forms cinched in red, like stained glass that decided to start moving. Nearby, SAMBA DE VERÃO snaps and swings on a bright saffron ground, pale blue-and-slate shapes stacked like cutouts, ringed in red and orange so the whole thing feels tuned and percussive. HAVANA SOUNDS, smaller but not quieter, is a 12-by-12 square of heat: a honeyed yellow field crowded with jewel-toned blocks, rust, teal, lapis, green, pressed tight.

Milder was raised downtown by the painters Sheila Schwid and Jay Milder, in a home where art was a language spoken fluently and argued about loudly. With two working artists as parents, looking closely was not optional, and neither was having an opinion. You feel that in the paintings. They do not charm you into agreement or explain themselves into safety. They assume attention is still a real act.

Pressed for heroes, Milder does not hedge. “Joan Mitchell, of course.” Then she gives a quick, almost apologetic add-on, like she is admitting to an inherited appetite: “I loved Chaim Soutine. I guess I love a lot of the artists my dad loves, like Georges Rouault, very strong painters.”

Her father, now 91, her earliest and most demanding teacher, pushed her toward Mughal and Persian-influenced Indian miniature painting, where saturation is not decorative and color is allowed to insist. In GREAT JONES, pigment behaves the same way: stacked, nudged, made to clash, then held until the surface finds its own logic. If you are tired of abstraction that plays nice, these paintings are a relief.

At CalArts, Milder went in through the side door, drawn to experimental animation and film because she didn’t want to take the obvious family gig. She worked with an Oxberry camera, animating frame by frame, until her mentor Ed Emshwiller watched her student films and said, “Rifka, you know these are the paintings.” She laughs. “And he was right.” She changed her major.

CalArts critique culture, she says, could be pitiless, especially for painters. “If somebody was new to the school and they were painting and they’re showing their work, it was like a gladiator pit.” People hammered them with questions that had nothing to do with paint. She mostly stayed out of the arena, sitting in now and then on John Baldessari’s Open Seminar. “I didn’t subject myself to that brutality,” she says, then adds, “Not that I was invited. I was an undergraduate allowed to observe.” She learned what she did not want: performance. No wonder GREAT JONES does not posture for the room.

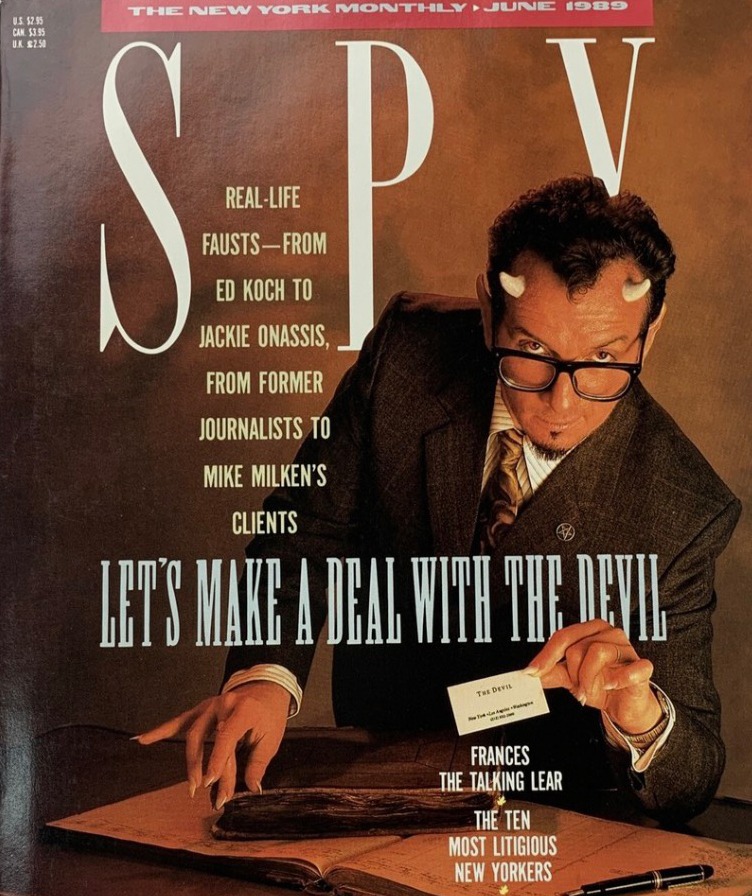

In the late 1980s, when she needed rent money, Milder designed a line of fancy ties sold in SoHo before the neighborhood went glossy. A Rifka tie landed on the June 1989 cover of Spy, worn by Elvis Costello dressed as the Devil. If you Google it, and of course I did, Costello holds a business card that reads “The Devil,” and the phone number on it (natch) is Donald Trump’s. “People were always asking me about the ties,” she says, laughing, “even when I was standing there as a painter.”

“I stopped,” she tells me. “I am a painter. So I kept painting.”

As a teenager, she dated Billy Harmon, a graffiti writer who tagged as SAGE. She never went with him when he painted. “Honestly,” she says, “back then I thought it was juvenile.” Then she gets to the part that still undoes her. “But I’d be sitting on the IRT, and I’d look up and see an entire love letter to me on the subway wall. I felt like I was hallucinating,” she says. “Am I really seeing this?”

That is the thing GREAT JONES holds onto: not the downtown brand people keep trying to sell back to you, but the lived, always-shifting feeling of the street itself, the daily recalibration of light and noise and pace. These new Milder paintings, unfazed by the churn, refuse to pose or plead, so that if you stay with them long enough, they begin, quietly, to speak.

Rifka Milder: GREAT JONES is on view at Helm Contemporary, 132 Bowery, 3rd Floor, through January 31, 2026. Hours: Tuesday to Friday, 11 a.m. to 6 p.m., Saturday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Follow @rifkamilder and @helmcontemporary.

About the writer: Laurie Gwen Shapiro’s new narrative nonfiction book, The Aviator and the Showman, about Amelia Earhart and her husband, George Putnam, was published by Viking on July 15. An excerpt appeared in The New Yorker in early June. She is currently at work on her next Viking book, Einstein in America. @lauriestories