I walked into the PPOW gallery the morning my friend Riki died. The 182-panel illustrated small drawings by New York artist John Kelly, which extend as an open graphic memoir around the gallery, captured me instantly, letting me in on a personal journey of mortality, pain, and beauty. There was something generous in the way Kelly handed his notebook and shared the manuscript of his injury. It resonated with my thoughts of investigating and dwelling on mourning and mortality.

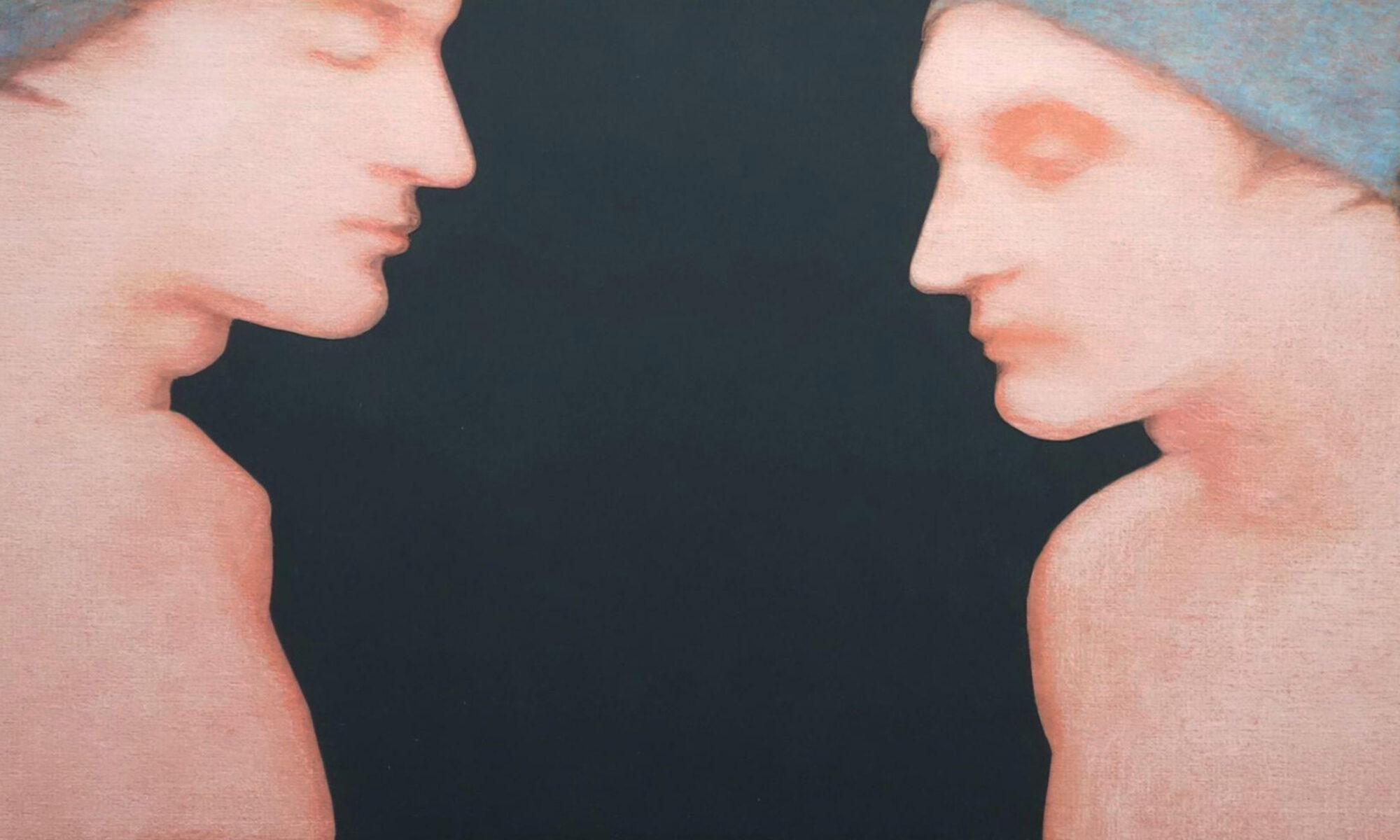

Kelly constructs his narrative from multiple sets of self-portraits accompanied by text blocks and contemplative abstract schemes. These begin with his idealized grand moment of performance that spirals unexpectedly. In 2004, Kelly fell from a trapeze and broke his neck, interrupting his life and practice.

Kelly created fine drawings that show amazing dedication to control of his chiaroscuro: although he is a performer and a dancer, and his practice was all about movement, these are not gestural drawings; they are careful and elaborate renderings. I imagined the contemplative process of starting to make them while lying confined to his bed. The perfect execution allows us to read them as if they were video stills extracted from his stream of consciousness. Kelly dwelled and doodled on them, like a noir detective, searching for clues and analyzing various angles of what led to the moment that changed his life.

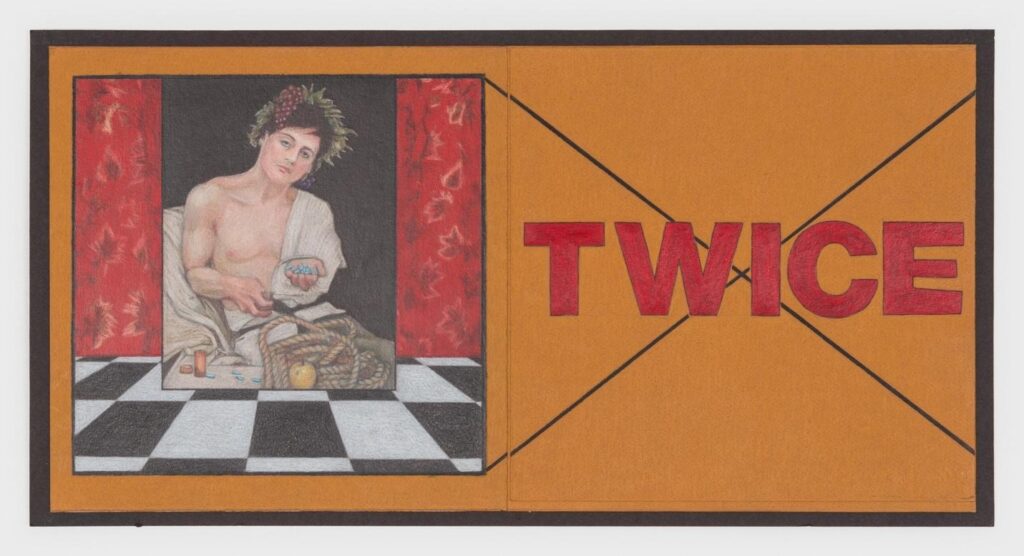

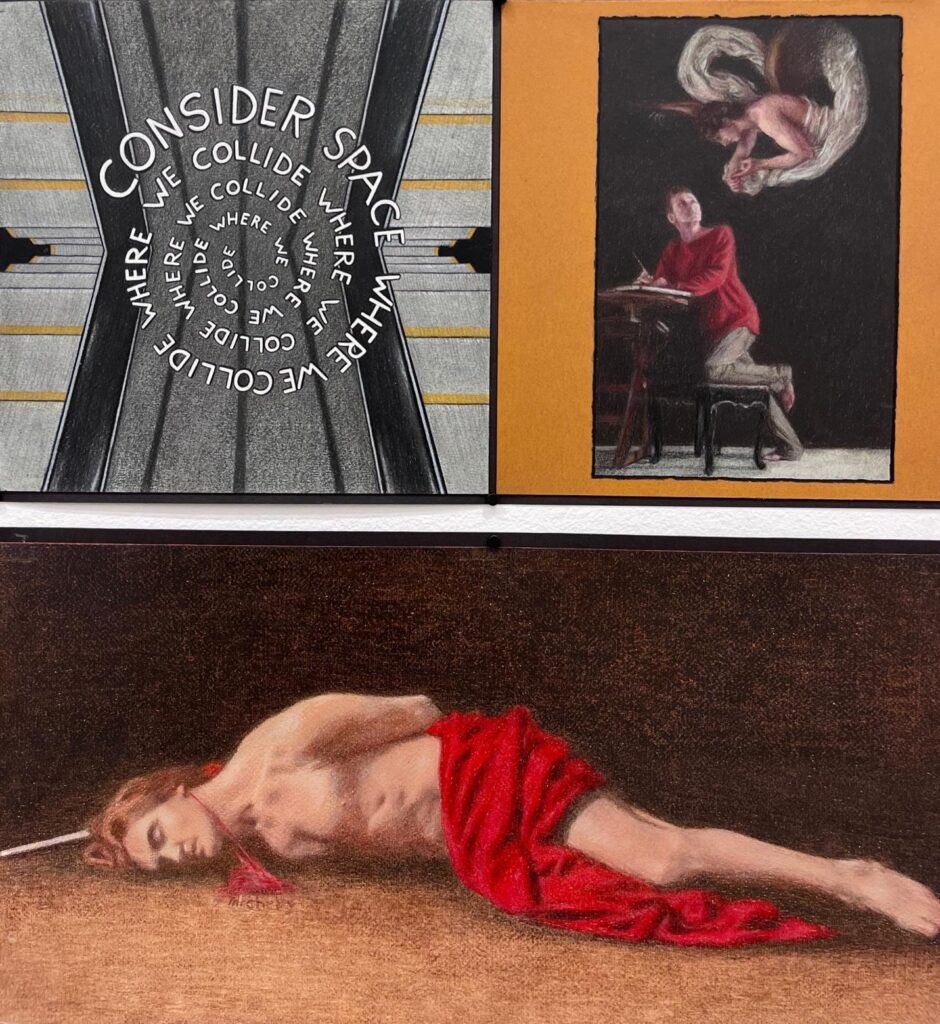

Kelly begins his sequence by adopting figures from Caravaggio’s paintings, which he sees in a book. He develops a set of portraits based on Caravaggio, a reenactment of contemplations on his graze with death. Kelly portrays a conspiracy, flamboyant night dining, a memory of beautiful, flashy young shoulders and flower-crowned youths, as if in a vulnerable dream. He imagines himself recreating the young figures as his mature self, keeping his drawing in the same color scheme of the light flash covered in blood-red fabric against the dark background. The Caravaggio-esque rendering functions as stage notes for the reenactment scenarios that become a new way to understand what led him to that fall.

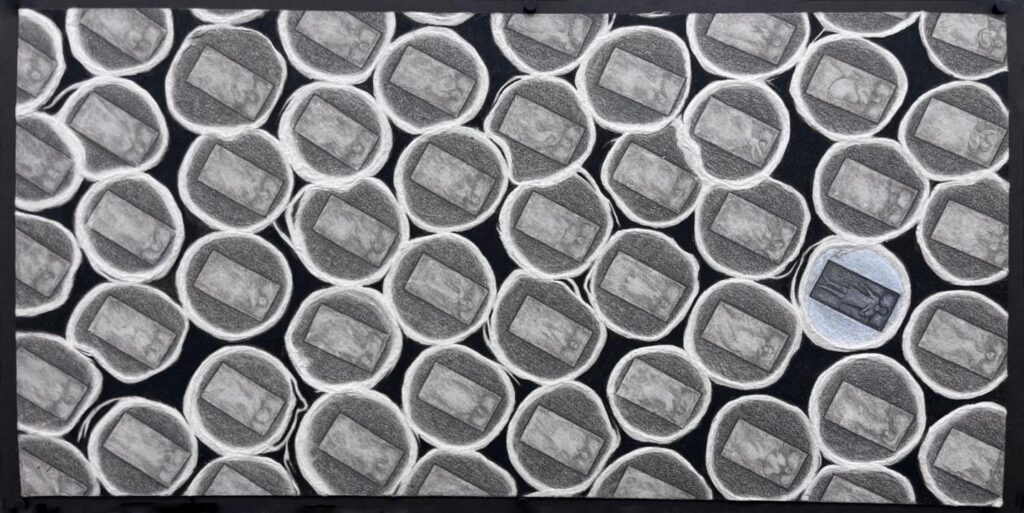

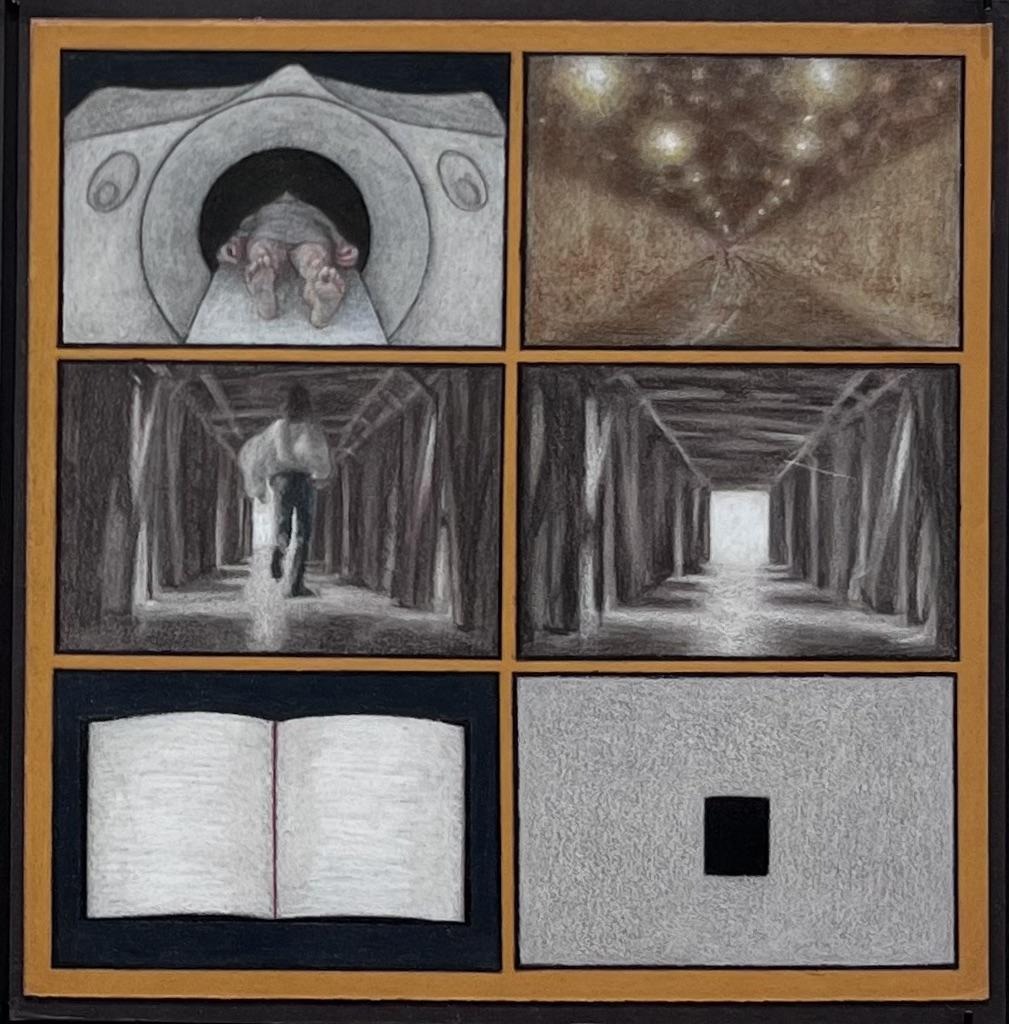

Following his accident, Kelly diverts in his portraiture in parallel new directions, as a way of dwelling on his accident from many aspects, searching for evidence. His previous performance drawings turn into horizontal poses as he is laying with a neck brace on a stretcher. He now continues with the lying figure, looking at it from a bird’s eye perspective, drawing himself in graphite, flat on a stretcher with his legs ajar and his arms straight, slightly open beside his body. He repeats this image throughout his work, trying to understand the abrupt change in his life. In a few of the drawings, he makes himself very small. In this version, he encircles his tiny figure on the rectangular stretcher, then multiplies it to create a two-dimensional cellular net all over the page, becoming biological and almost unrecognizable.

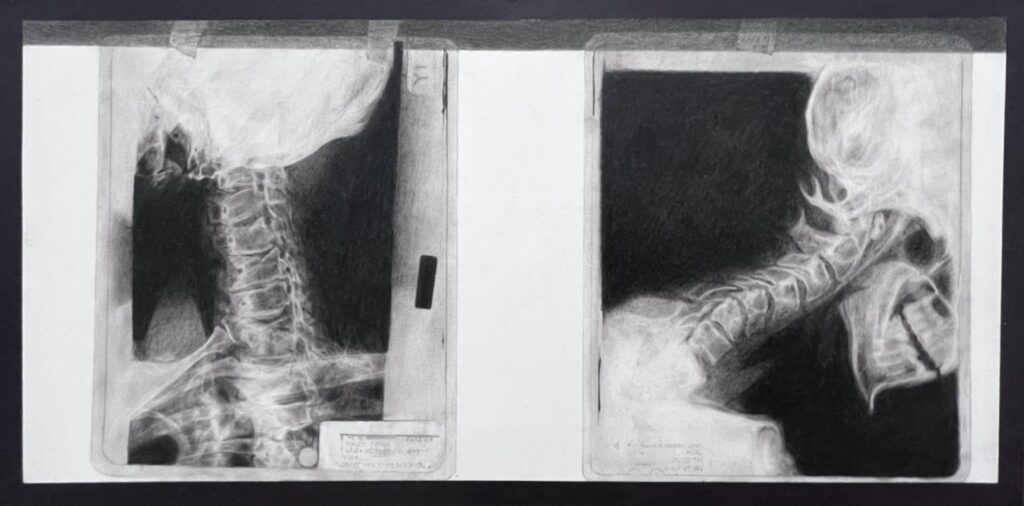

In another stream of thought, Kelly draws his body from the inside. Using his medical results, to reach and investigate into parts of himself that he cannot see, making monochromatic drawings of X-Rays of his curved spine.

The white-on-black rendering of his spinal profile X-rays is especially commendable as he manages to express the translucent quality of the original medical film using crayon on paper. Kelly goes over and over again into this medical portraiture annotated by his own medical records, continuing with his process of looking for some evidence. His skeletal drawings are displayed in the exhibition next to his dark and red Caravaggio drawings. There is new vulnerability in this juxtaposing, as he gives up his performing persona, taking off his regalia to go beyond the familiarity of his performance language into the cold scientific imagery that is colorless with translucent facts.

As the world of his injury takes on the rest of the narrative, Kelly makes poetry out of the medical. He adds to the X-rays also other procedures. He renders the round MRI chamber like a contemporary shrine. In his small drawing, he manages to turn that medical device into a mythological purgatory, reflecting on his sense of tunnelling to peek at mortality.

Drawing himself being wheeled it into the MRI chamber, he chooses a feet-on perspective. Looking at his own body being wheeled to the checkup, he repeats and elaborates on it. Placing himself on what looks like an operating table, exposed, foreshortened, he becomes even more vulnerable.

This process of drawing from photos that are available to Kelly after his injury creates a sense of transformation of the figures into objects as we are going through his diary flow. Starting with the book his friend gave him and continuing through his medical experience, we follow a colorful rendering of some scenarios and are captivated by the texture of the colorless medical film, turning his own skeletal bones into a still-life memento mori.

A FRIEND GAVE ME A BOOK by John Kelly, PPOW Gallery, 392 Broadway, Tribeca, NYC. On view until February 21st, 2026. Tuesday – Saturday: 10:00 am – 6:00 pm.

About the writer: Michal Gavish explores in her art and writing the world of art inspired by science, which connects to her previous career as a PhD research scientist. Over the past few years, she has written regularly for SciArt Magazine and SF Art News. In addition, she published several peer-reviewed articles, including an art publication at UK Intellect Publications and many research articles for scientific journals, including Science magazine. She has been working as an artist and art writer since she received her MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute in 2008. In addition, she teaches college art and science and lectures extensively on art history and on art in the Middle East, including several series at the Jewish Museum in San Francisco. @michalgavish