Downtown in Tribeca, beneath the Derek Eller Gallery, the George Adams Gallery sits like a quiet afterthought. Easy to pass by. Down a short flight of stairs, away from the street glare, Elisa D’Arrigo’s recent sculptures gather in a small white room and hold their ground. The scale is modest. The presence is not.

D’Arrigo’s sculptures arrive with a posture. They lean, slump, brace, and settle. A shoulder where you don’t expect one, an opening that reads like a held breath, a bulge carrying its weight low. Each piece feels as if it located its stance through a series of negotiations with gravity. Not a struggle, more a lived-in agreement. Gravity as a collaborator.

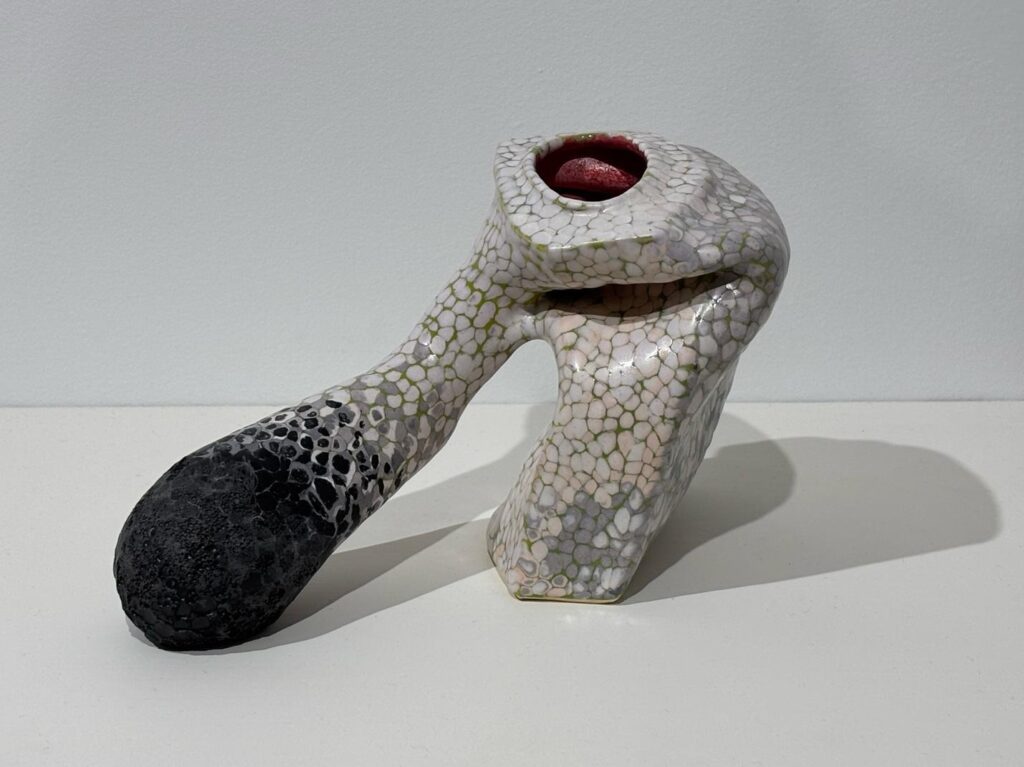

You approach one, and it seems mid-gesture. A thick, rounded form tilts onto a tubular extension like a body leaning on an elbow at last call. The posture carries a kind of drunken resolve. I caught myself laughing. For a flicker, it read like a plucked roast turkey staging an escape from the kitchen, headless and determined, sneaking away from its appointed fate. That oscillation—abstraction slipping toward figuration and back again—is part of her language. The sculptures never land on illustration. They hover in recognition.

It would be easy to situate D’Arrigo with Ken Price and Ron Nagle. The intimacy of scale, the devotion to surface, the understanding that a small object can hold a large presence. Price opened clay to the intelligence of color and painting. Nagle showed how a sculpture the size of a coffee mug could command a room through precision and theatricality. D’Arrigo accepts those inheritances and moves on. Her palette leans fleshy, mottled, alive. Her pointillist skins gather color in droplets and fields that breathe with the form. Gloss, satin, and dry passages move the eye across the surface. The skin belongs to the body. What distinguishes her work is a maturity of form. These sculptures do not read as demonstrations of ceramic possibility. They read as sculpture, full stop. Clay feels fully digested into the thinking.

A more telling lineage runs through post-minimalism. Eva Hesse lingers here in spirit—in the way form feels discovered rather than imposed, in the sense that material records touch, time, and decision. D’Arrigo’s seams, hollows, and shifts in mass carry that same feeling of encounter between artist and matter. The clay has been listened to. Process stays visible as a trace of attention.

There is also a Bourgeois-like understanding that a form can suggest a body without depicting one. A protrusion can feel comic and tender at once. A lump can carry pathos. D’Arrigo’s works live in that zone where the bodily exists as a condition. Torso, organ, creature, character—these readings pass through the mind without settling. The sculptures keep their autonomy.

And then there is Hieronymus Bosch somewhere in the background—the old allegorist of hell on earth, of human appetite wandering loose. His worlds were crowded with tiny beings and dramas of desire and consequence. D’Arrigo’s forms feel like distant cousins to those beings, pared down to posture and mood, carrying their odd humanity without the punishment narrative. These are not sinners on display. They are small beings navigating their own impulses, their own gravity.

Her knowledge of clay shows in timing and risk. Openings hold tension after firing. Thickness shifts hold. Glaze activates rather than dominates. This comes from years inside the material—chemistry, heat, failure, and adjustment. Many artists approach clay for its immediacy and its social warmth, and that enthusiasm has its place. D’Arrigo’s relationship reads deeper and quieter. Skill here serves expression. Craft serves form.

The demeanor of the work lands close to the emotional weather of now. Joan Didion once wrote in Slouching Toward Bethlehem about a generation coming into consciousness with a sense that the center was not holding, that innocence had already slipped away. D’Arrigo’s sculptures carry a similar awareness, though on a personal scale. Her characters feel tired and determined. A little inebriated. Groping in the dark, I had a feeling I’d met a cast of characters—comic, stubborn, slightly demented, fully human—who understand more about living in a crooked world than any of us mere mortals might let on.

Out of Hand: New Ceramic Sculpture at George Adams Gallery

On view through February 28, 2026. @georgeadamsgallery

About the writer: Andrew Cornell Robinson is a New York–based artist, writer, educator, and sometimes curator, whose practice centers on ceramic assemblage and painting, grounded in over four decades of work in ceramics. He studied at the Maryland Institute College of Art and the School of Visual Arts and completed an eight-year apprenticeship at an Anglo-Japanese pottery, developing expertise in Raku kiln building, glaze chemistry, and production methods. His work treats material as a carrier of memory and cultural exchange, bringing painted image and fired form into charged proximity. Robinson runs a ceramics and interdisciplinary studio in Queens and has exhibited internationally, including with the UK Crafts Council and in India and Haiti. A 2026 NYSCA Artist Grant recipient, he is preparing a solo exhibition at Equity Gallery in winter 2026. He teaches at Parsons School of Design and Drew University and writes on contemporary art and craft. www.andrewcornellrobinson.com @andrewcornellrobinson @acrstudio