The paintings in James Gold’s solo show, Infinite Scroll, act as intermediaries between past, present and future. These glimmering grids at Morgan Lehman gallery toggle between his deep reverence for history and his active aesthetic imagination. Talking with the painter about his wider practices in collaged artist books and archeological renderings revealed new means of perception and applications of art-making.

Will Kaplan: The work of Infinite Scroll seems to concern time. Tell me about their lifespan, from ideation to execution?

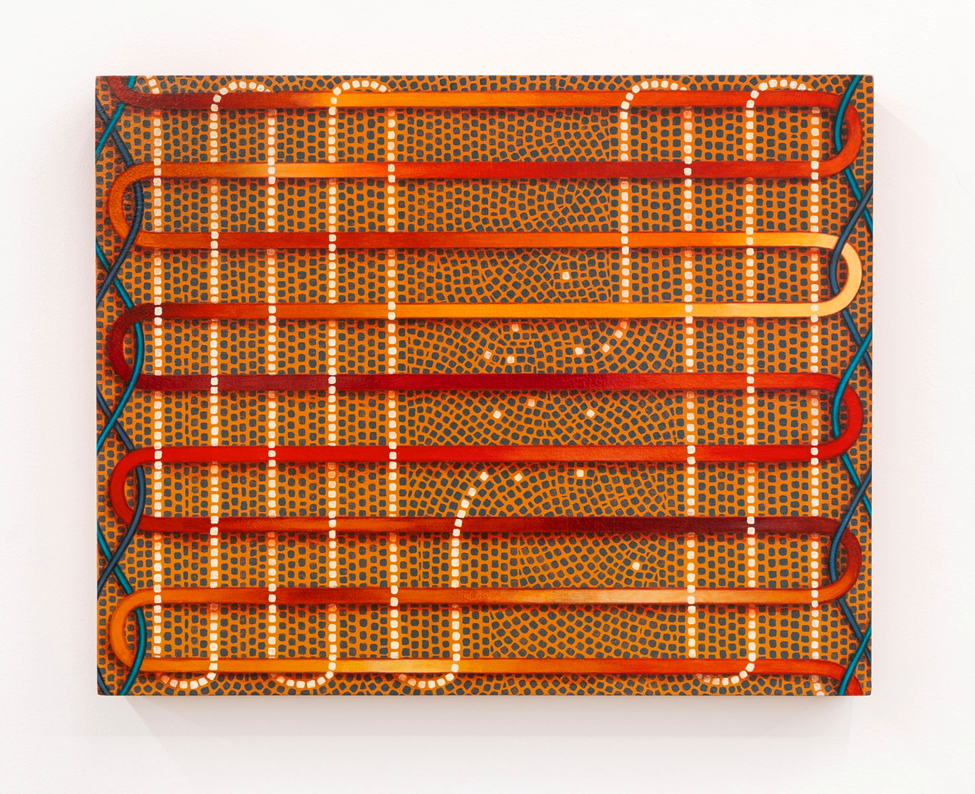

James Gold: I usually have maybe five to ten paintings in progress at any time, and I jump between them. Some of these took, maybe eight, nine months. Sometimes it’ll be a little faster. Like Mosaic/Tapestry was pretty fast, maybe a couple weeks, because that was the last one I made before the show. I wanted something that ties it all together. I definitely have some clear plans for paintings, but then also let things change as they go along. Some of them will start off as drawings, or the drawing will be one element. Oftentimes a vision enters my mind, and I wonder, how would that look as a painting? I won’t know until I make it. That’s a lot of the excitement of wanting to create these things. A lot of them do have an artifact feel to them, even though none of them are actually real artifacts that are out there in the world. They are invented.

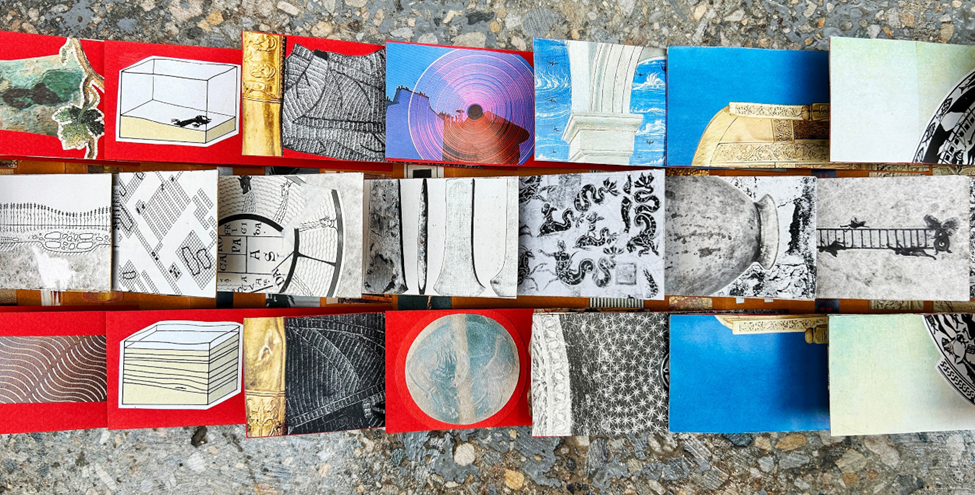

When making my collage books, on the other hand, I have thousands of little scraps. I’m always pawing through these bins of second hand books, which are filtering through my mind.

WK: I understand you quote from historical and craft diagrams, are those a frequent starting point?

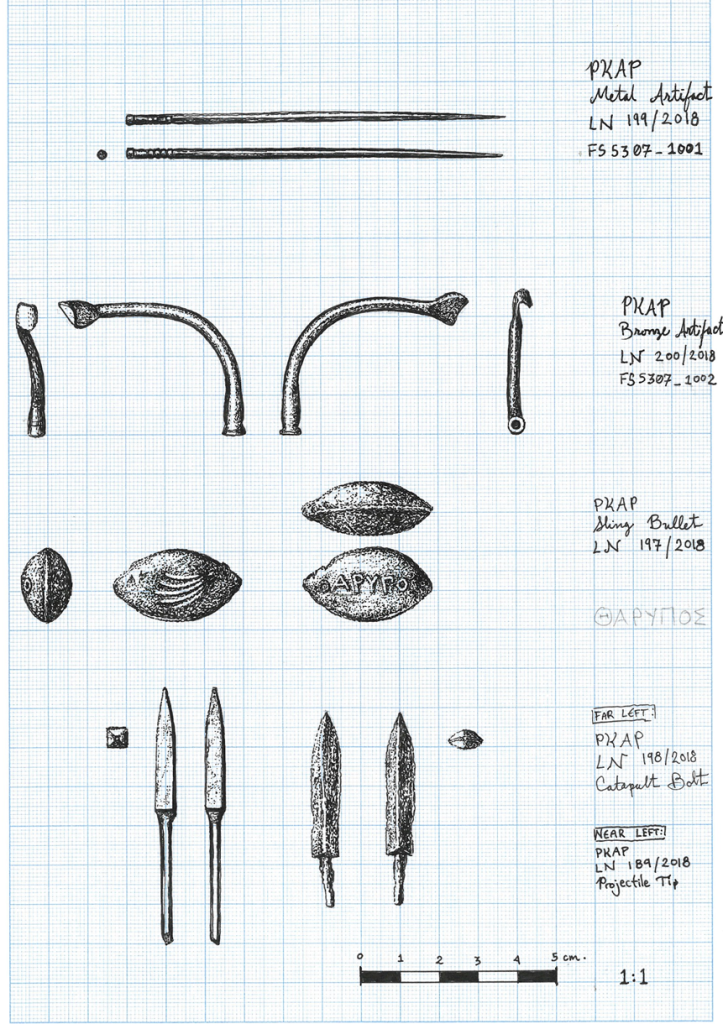

JG: Not always, but I do enjoy the crossover from a technical diagram to a painting. I’ve done work in an archaeological dig, where they want very diagrammatic drawings. I had to capture the surface texture and the contours of these artifacts. I wound up thinking of it as a map of the surface. So I think a lot about maps, diagrams, cross-sections. They’ll take a photo of an archaeological site and then impose a grid on top of it: gridding out each segment of a pit. That’s an overlay of the creative over the reality, or a diagram of a reality.

So I go from these references of very simple drawings, and then envision: what if they were interacting with colorful mosaics? I am drawn to the imagery of both tapestries and mosaics, even though I don’t really make them. But this work lets me make a mosaic with paint, make a tapestry with paint. I like the freedom of making these things a little bit between a tapestry and a mosaic. It becomes this mysterious material that doesn’t or can’t exist in the real world necessarily. It’s sort of hard but soft at the same time.

WK: So tell me about the process and materials.

JG: I’m always adding new techniques to my arsenal. But for the most I’ve been using this very sandy textured gesso with visible cellulose fibers. A primed panel then almost feels like a piece of sandstone. To paint the image, I use an acrylic gouache or matte acrylic. I may do a bit of detailing with india ink. It’s all very absorbent, which is nice for doing egg tempera on top of. Sometimes I’ll work back and forth between the layers and materials . For years, I was just doing egg tempera, super traditional, which was a good way to learn. But now the egg tempera is always the very last layer. The cherry on top. It’s how I get the colors exactly how I like them.

This time around, I got to experiment with the mosaic tiles. I made a little stamp, dipped it in paint and stamped it on the panel, which I’d never done before. I was trying to figure out, how do I make this a mosaic? I tried it with the brush, but the brush mark didn’t seem right somehow. But this stamp really worked for me.

WK: And how about the collage books?

JG: The collage is a bit like my drawing practice. It’s good for working through things or combining things in a slightly faster way. The book is how I arrived at the dimensions for Interlace II. It corresponds to the proportions of the book. I wanted to make a panel at the exact proportions of this page and then map the image onto it. So I’m definitely thinking more and more about moving from the book to the painting and back and forth.

Originally I was just going to have the book on display during the opening. And then we decided that we might as well just keep it on display. I’m not sure if it’s an official part of the show or not.

WK: It’s the bonus track? The in-person exclusive?

JG: Exactly. It’s an important part of my practice. I would say it’s analogous to a sketch pad for me. It’s a nice palette of things that I feel less authorship over, but in a good way. There’s a freedom to it. It activates parts of my imagination just through working. I feel very drawn to found materials that have a sense of chance or unpredictability.

And I feel like there’s a balance of that chance with the way I usually work. I’m very methodical. I think, all right, I got this plan, I’ll execute it. So I’m always looking for more ways to involve chance, or to be surprised in the studio.

WK: Moving out of the studio, could you share about your experience at an Archeological dig in Cyprus and the work you did for the Larnaka Archaeological Museum?

JG: Yeah, I was talking with the chief archaeologist to create some reconstruction drawings of this dig site. He told me what this ancient fortification looked like. We were going around and seeing this structure from different angles. How the walls would have been this high, etc. They wanted a view drawn from this sort of path sloping up a hill and showing where there was a fence carved away. To me, it looks like a hill with nothing on it, but the archeologists are able to see and imagine these structures that were there. I was making the invisible, visible again.

WK: Wow. And then within the museum, you were creating studies of the excavated artifacts. I understand you used a stippling technique with a micron pen?

JG: Yes, the drawings are preferable to photos for them. Everyone asks why don’t they just take photos? It’s really the clarity of the drawing that they want. A photograph of these things will often look like a lump of metal. But if you do a drawing, you can see some things like incised lettering. In a photo they would just sort of disappear.

WK: That feels related to Infinite Scroll, where you’re thinking of the mosaic tile as the digital pixel, the unit or the bit of information. In that instance, it’s the single pen dot. The drawing or the diagram is more simplified than the photo, but more illuminating. We get more information through reduction.

JG: Yes, exactly!

WK: And I understand for this method you used callipers and grid paper to create a one-to-one reproduction.

JG: Yeah, it’s always a millimeter grid paper. It was fun to have a little object and then measure it and transfer that back and forth, which isn’t how I would normally draw anything. It was very freeing to get back to regular studio work after that. After the rigidity of all these conventions where there’s a standard angle, and you can’t invent anything.

WK: Were you working with the grid in your own work before using the millimeter grid paper?

JG: No, I think it’s a big part of getting very into the grid with this work. I find the grid very satisfying. It’s kind of calming too or a little soothing. It’s a way to make the world feel a little bit manageable. I just got to go square by square on this.

I also like that it makes the rendering process more mysterious too. It might be a more familiar image like Compression Field, which is a specific pattern. But in gridding it, you can’t quite tell where it’s from. Its origin is a little bit pixelated or a little bit shrouded in mystery.

I was looking at my book pages, and thinking, ok I could paint it in a very illusionistic way if I wanted to, but I found that a little bit overwhelming. So I simplified it into the grid instead…But then again I don’t know if it would have taken me any longer or not. By the time I line the grid and paint every little square and paint over it again and again to get it just the way I want, I don’t think the grid is necessarily a time saving device.

All images courtesy of Morgan Lehman Gallery and the artist

Infinite Scroll, Morgan Lehman, 526 West 26th Street, Suite 410. Through October 18th.

About the author: Will Kaplan is a Queens-based artist and writer. His work has been shown at the Spring/Break Art Fair , Pete’s Candy Store, and on Governors Island. He has written for Artspiel, Copy, and Passing Notes.