For many years now, John Avelluto has used trompe-l’œil and sculptural hyperrealism to unsettle the stereotypical trappings of Italian American identity, particularly its relationship to food. As in many other migrant communities, food functions as a vessel of memory and belonging, often bearing a disproportionate symbolic charge. Avelluto’s lifelike slices of acrylic mortadella and mounds of rainbow cookies confront this issue directly: they turn the charged history of foodways and their role in shaping communal narratives into something at once seductive and ridiculous. Viewers are forced to contend with the absurdity of articulating an entire national identity through piles of candies, pastries, and cold cuts elevated to the status of icons.

Avelluto’s latest research, which I encountered at his exhibition AI e IO: Recent Works by John Avelluto moves into more unsettling territory. This show, beautifully curated by Dr. Caterina Pierre at the pristine, postmodern hall of Kingsborough Art Museum, prompts questions about the foundations of knowledge that underpin our sense of belonging to a family, a community, and a national identity. In order to pose these questions, Avelluto introduced artificial intelligence in his practice as a tool to probe some longstanding assumptions about remembrance, storytelling, and bearing testimony. What does it mean to “remember” when memory is no longer grounded in experience lived or received, recalled or revivified in accordance with moral and ethical bonds? How does a fictional memory compare to the organization of past facts, circumstances, affects and relations that inform our identity as individuals and groups? Which broader social and political implications emerge from the use and misuse, acceptance and rejection of these artificial memorial accounts?

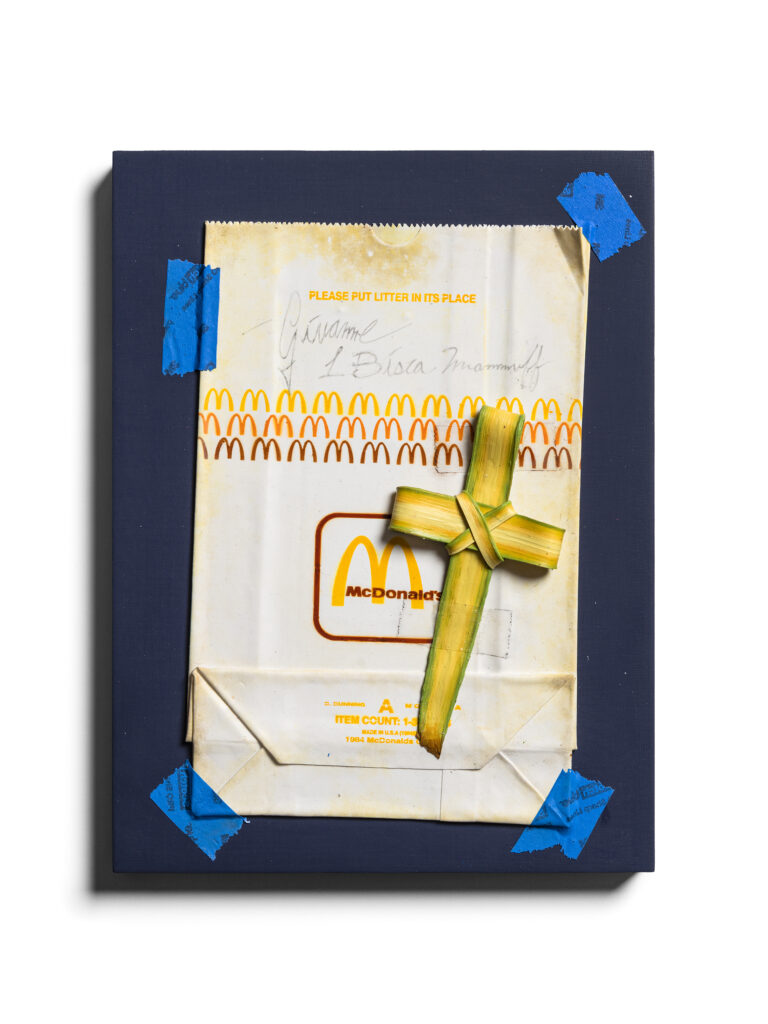

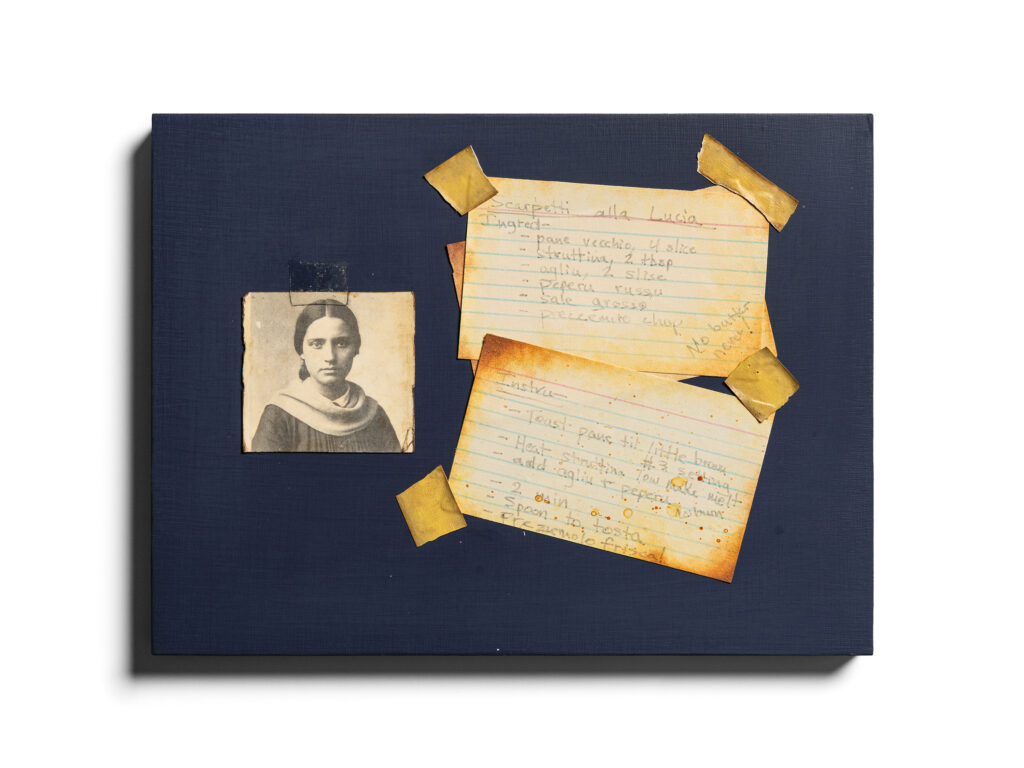

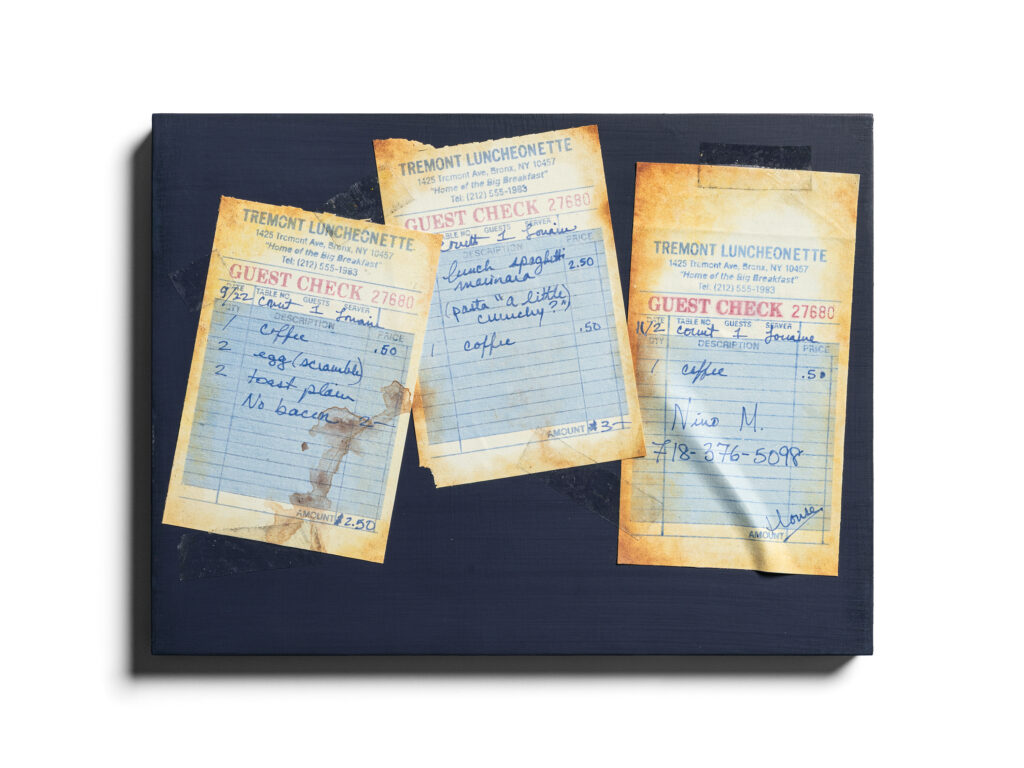

Avelluto’s experiment is carefully planned and executed. A viewer encounters three tableaux affixed on a wall, each embellished with fragments of Italian American life. One includes the black-and-white photograph of a grandmother, along with culinary recipes handwritten on index cards; a second includes a vintage McDonald’s takeout bag, overlaid with a Palm Sunday crucifix; the last one showcases yellowed guest receipts from a diner on Tremont Avenue in the Bronx. Each element is painstakingly rendered in Avelluto’s signature technique, built patiently through layers of acrylic paint. As such, each is also entirely fake: a souvenir of a memory that does not exist.

Below each assemblage, a wireless speaker plays a recorded voice narrative on an endless loop, similar to those a visitor might encounter in any museum preserving an oral history archive. The human voices animating these narratives are generated by artificial intelligence, as are the narratives themselves. While Avelluto offered a few coordinates to the AI model, suggesting some elements of these retellings, it is the machine that fabricated and wove them into plausible narratives, inventing genealogies and supplying them with saccharine emotional texture.

In one instance, titled Nonno Corrado, the process is loosely anchored to a real episode preserved in family lore: Avelluto’s grandfather’s habit of purchasing breakfasts at McDonald’s, which he referred to as “Madonnahs”, a distorted pronunciation the artist drew from lived memory. Beyond this anchor, however, narrative invention takes over. The artificial oral history illustrates how a Palm Sunday breakfast became a surreal convergence of liturgy and fast food, condensing Catholic ritual, immigrant improvisation, and consumer culture: “He was standing in the doorway holding two palms in one hand and a sack of Egg McWhatevers in the other, like some kind of immigrant saint of breakfast.” Likewise, false quotations containing linguistic artifacts such as “colazione sacramentata” or “È tutto benedizzatu”, echo the ways in which Italian immigrants who spoke primarily a regional language or a dialect might have expressed a concept, exaggerating the process into parody.

A similar operation structures Lucia Scarpetta, where the AI model produces an immigrant narrative without any factual reference. Lucia Scarpetta supposedly comes from Montebianco, “this tiny little place… up in Calabria,” a village that does not exist and where, fittingly, “we had nothing, but we had everything”. The story hinges on symbolic objects, “a shawl and this old copper spoon from her Ma”, imagined as Lucia’s sole possessions upon arrival at Ellis Island. The spoon story is implausible and yet immediately legible, drawing on a long tradition of migration mythology in which material poverty is redeemed through emblematic objects or circumstances. As a matter of fact, Lucia Scarpetta’s redemption in the New World comes from her invention of “Scarpetti alla Lucia”, a recipe for toasted bread with lard that is a mere inversion of her name—a linguistic shift that transforms the persistence of scarcity inscribed in her persona into a new system of memories and traditions for a new generation of grandchildren.

In the third piece, Nino Mancuso, AI assembles a social geography dense with historical signals: a job at the docks in Red Hook and labor unions; a crowded apartment off Arthur Avenue in the Bronx; a phantom luncheonette on Tremont Avenue. Nino meets Lorraine, an African American woman “reading Blues People between customers,” and the story leans deliberately into interracial encounter. What is striking here is how AI compresses complex personal histories into recognizable tropes. Dock labor becomes synonym with masculine endurance, the Bronx borough becomes a stage for ethnic proximity and stereotyping, while interracial marriage becomes a proof of openness. Conflict resolves through stoic pragmatism, culminating in a “Winter of 1997” lobster-sauce fiasco, an episode from Avelluto’s actual family lore that artificial intelligence plunders and redeploys with its typical appetite for hallucinated certainties and oversimplifications: “We got garlic. We got oil. That’s enough.”

Avelluto’s work intersects productively with some of the themes discussed by Avishai Margalit’s The Ethics of Memory, in which the Israeli philosopher questions what it takes for social formations of individuals to become communities of memory, where the labor of memory (its preservation, study, interpretation and transmission) is sustained by scholars, intellectuals, institutions, rituals, groups, and individuals at large. Artificial intelligence has no real place in a community of memory in any traditional sense. Surely, the machine can access and process through statistical evaluations the same wealth of shared memories about immigration that we, too, have lived, read, or heard about. AI cannot, however, participate in the ethical bonds that distinguish a shared memory from mere information: it takes no responsibilities, it does not recognize itself in the memories of others, it feels no moral obligation to remember with others or for others. The machine’s overabundance of narrative details is mirrored by its utter lack of concern for losses, errors, and outright fabrications.

What emerges from Avelluto’s experiment is a narrative form that exposes the limits of what some scholarly papers have begun to define as synthetic memories—uses of generative AI to reconstruct or preserve memories of individuals dealing with aging, trauma, loss, or displacement. Synthetic is an apt term, as it evokes the epidermal sensation of synthetic fabrics that follow the shape of traditional clothes, but feel different when in contact with our skin. While limited uses of this technology might yield positive outcomes in medical or therapeutic contexts, the moral bonds that sustain communities of memory are quietly eroded by a narrative form of remembrance that proceeds without accountability, attachment, or remorse.

Avelluto has invoked concepts found in Yuk Hui’s Recursivity and Contingency in the genesis of his recent work, pointing to the risk that algorithmic systems and established loops lead to falsification and stabilization into commercially packaged narratives, ready for mass consumption. The artist’s hope is that his work can also point to whatever natural and alive remains in or can emerge from these narratives, treating the presence of contingency as a critical resource: the disquieting suspension of disbelief that these tableaux require leave open the possibility of something unscripted and ultimately human to appear—if not in the works themselves, at least in the viewers who interact with them.

While trompe-l’oeil dissimulates its conceptual preoccupations behind a veil of obsessive adherence to hyper-realistic representation, Avelluto’s trompe le pensée via artificial intelligence presents its questions more directly, illustrating the extent to which personal memories and group identities are dangerously predisposed for intrusion. Avelluto’s memorial takes on Italian American identity and its clichés are a model for broader reflection on how contemporary subjects are increasingly invited—by technology, culture, politics, and the economy alike—to inhabit identities that are pre-shaped and predictable.

Diasporic identities, national narratives, and family lore already rely on repetition and symbolic shortcuts: the risk of handing over the labor of memory to artificial intelligence removes a moral safeguard that won’t be easily reintroduced, along with the communal bonds that once grounded these identities and narratives. What remains to be seen is whether we will retain the capacity to perceive and act upon contingency, to tear synthetic memory at its seams when we suddenly realize that it fits too well, or worse, that it has made us into caricatures.

AI e IO: Recent Works by John Avelluto

Curated by Dr. Caterina Pierre at Kingsborough Art Museum.

On view until February 4, 2026

About the writer: Nicola Lucchi received his Ph.D. in Italian Studies from New York University in 2016 and taught Italian language, literature and culture at Dickinson College and at CUNY’s Queens College. He served as Executive Director of the Center for Italian Modern Art (CIMA) in New York, managing the Center’s exhibitions, cultural programs and its Research Fellowship for graduate and postgraduate scholars. In 2024, he became Director of Research and Education at Magazzino Italian Art in Cold Spring, NY, where he oversees the Library, the Fellowship Program and the museum’s publications, as well as the activities of its Education Center. His research has appeared in scholarly journals, edited volumes and exhibition catalogues, with a focus on Italian Futurism, the dialogue between poetry and the visual arts, and the work of Bruno Munari. He has curated exhibitions on Futurism, political propaganda, avant-garde advertising posters, Italian interwar architecture and Piero Manzoni.