A clamor of murmurs without end. Several ghostly strands twisted strangely yet remained formless, wispy, and clinging, yet never settling into anything definite. Moving, then halting; halting, then moving again. Soft as if boneless, without body heat, yet inducing a tremor from within: a sudden burn, gooseflesh blooming in patches, sticky, viscous—caught and entangled by a reckless surge of ghostly energy. One slips from the ordinary into a hollow. A Lure, A Lament offers, at first encounter, precisely such a sensation. And yet its murmuring voice continues to drift, recounting wave after wave of fragrant air.

Curators Weifan Mo and Shuhan Zhang compose a piece of tender yet violent speech, an intimate outcry. They state, without euphemism, the inescapable proximity between spirits, ghosts, and the living masses; and, like a gecko severing its tail, they wrench at the obsessive entanglement between ghostly figures and the female subject, as forged by patriarchy. Their text, serpentine in its subtle—long, sinuous, lifting its head, hissing again and again, burrowing ever deeper. I realize that something has begun to spiral slightly out of control: snakes, ghosts, women—each pointing back to their own images and the residual shadows of language. Familiar scales, never fully drying out. The female curators and artists are deeply versed in this iconographic system sedimented within decay: to be seen, to be recognized, to hover between distance and intimacy—only to dissolve. Yet here, in this moment, the manifold apparitions of what is said to be “haunting” completely disrupt the constructor’s private hypothesis. “Something’s possessed,” someone mutters.

Placenta, funeral, longevity, blessing, night escape, fragrance—you recite the works from the titles softly, almost involuntarily lowering your voice, sensing a tangible dimness and unease. Repeatedly lifting your eyelids, you find canvases and works on paper wavering atop wooden furniture and plinths, suffused with a dense, indecipherable dust-smell and a classical legend incarnate: old objects summon ghosts; ghosts summon old objects. The wood retains the height and scale of daily use. Each work is propped and lifted into a position suspended between reverence and abandonment. The faint glow they emit carries something of pulverized gospel, like stalactites or weeping willows, seeping and drooping. “None can withstand the rain,” you echo.

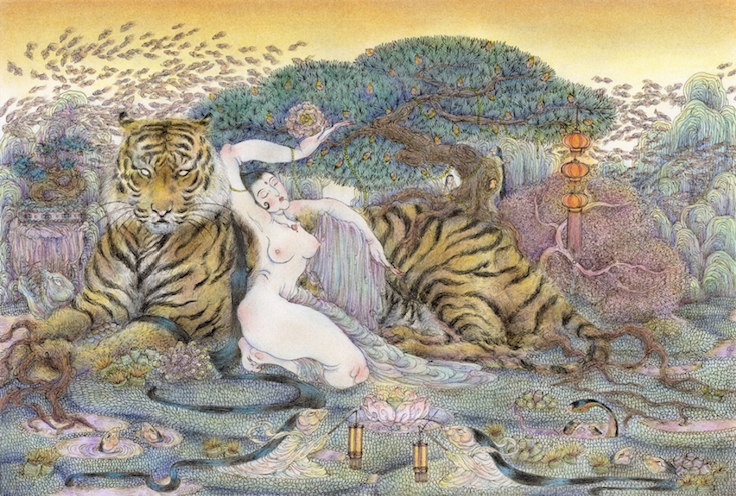

In Mosaz Zijun Zhao’s works, lush and supple goddesses slowly turn in her sleep. As figures of metaphor, they share with the pantao (蟠桃)—the peaches of immortality—a bloated sweetness both absurd and sacred, endowed with an inviolable sanctity. The fine parting of hair, the auspicious mole between the brows, carries an attachment to—and a mournful recognition of— “a bodily experience never truly modernized.” In a drunken cadence, they weave dream-interpretation diagrams beyond the shrine. “A dream within a dream.” The maternal body no longer merely sustains mythic origins; it spills outward, fluid and luminous, continuing to secrete. Saliva becomes strands of hair, gushing forth from grand, swollen depths to moisten paradise and bed, unable to sever the ever-renewed bonds of attachment and the cycle of life and death.

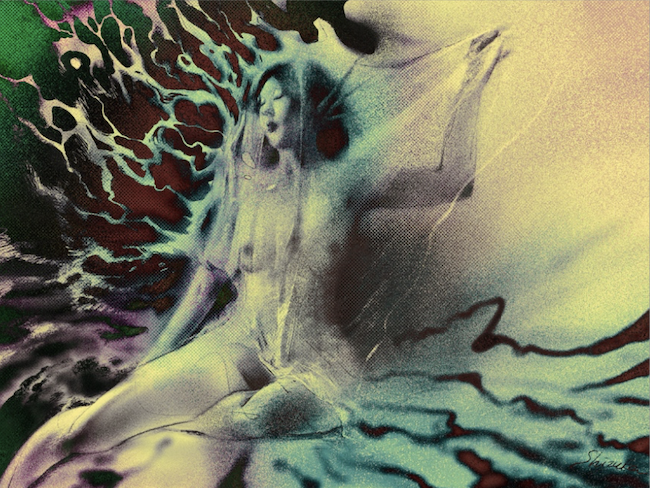

When the works of I Chin Sung intervene, this drunken dream begins to be irradiated. Guanyin Bodhisattva figures, spirit tablets, bodies, and faintly legible fragments of text stream outward in urgent, radial flows along the meridians. The meridians are iron-boned, hoarding light; yet they also resemble scattered comb teeth, bearing sharp, vivid experiences of life and death stored within. These images mediate one another, forming an inward-turning path of illumination: language gradually reveals its structural weight, family tradition, and lived suffering, and Buddhism interlocks tightly with them, together shaping a warmly illuminated yet oppressive shadow that flickers beneath the lamp.

Yike Li extends this radiance, engaging in dialogue with Mosaz’s A Joyful Funeral. Through etching, myths and the imperceptible trace of fragrance are carved with unwavering resolve. Linear expansions—willow-like, yet cursed in rhythm—repeat incantations and ritual reenactments through the medium’s inherent reproducibility. Within the ravines of the etched grooves, spirits and ghosts sink deep, unable to Ye Ben (夜奔, “night escape”). The limbs and bones we now behold seem to convey the chaotic will of ghosts with moth-like eyes. The fluttering sound is pressed beneath stones, yet it leaks into the viewer’s restless eyes. Viewer and artwork alike become moths, trapped within an inescapable genealogy.

Thus, with light as riddle, symbols as snare, and fulfillment as trail, the exhibition, in its sultry whispers, subverts the traditional allocation of the female ghost to either sensual delight or sorrowful lament. It allows ghosts to come and go, to escape the passive condition of being merely “summoned.” In Tao Yuanming’s The Peach Blossom Spring1, villagers warn the visitor never to disclose the place to the outside world. He breaks his promise and forever loses the path. This exhibition is both like the tale and against it: she says, tell the world if you must, return if you will—may you labor in vain.

About the Writer: Rui Jiang is an independent curator and writer working between Baltimore and New York. She holds a Master’s degree in Curatorial Practice from Maryland Institute College of Art. Her research moves between semiotics, intimate gestures, and shifting dialogues, examining how art forms deconstruct and reconstruct within a polycentric field. She investigates the tensions embedded in exhibition-making—complicity, reflexivity, and the shifting power dynamics that shape artistic discourse. Through interdisciplinary approaches, she experiments with curatorial strategies that challenge linear narratives, embrace contradictions, and reimagine the relationships between artists, audiences, and institutions. @secretary37_

A Lure, A Lament at Gallery 456, 456 Broadway, 3rd Floor, New York, NY 10013. Monday – Friday 1-5, Saturday 2-5, through January 30th, 2026.

- The Peach Blossom Spring (《桃花源记》) by Tao Yuanming is a Chinese fable from 421 CE about a fisherman who discovers a hidden, utopian village.

↩︎